Research School Network: Classroom Management and Self-Efficacy – a complex relationship How does self-efficacy influence teachers ability to implement classroom management strategies and what can be done about it?

—

Classroom Management and Self-Efficacy – a complex relationship

How does self-efficacy influence teachers ability to implement classroom management strategies and what can be done about it?

Share on:

by Durrington Research School

on the

So, we are nearing the end of the first month back, and for many of us, much of this time will have been spent attempting to embed classroom and behavioural routines; whether this is on a whole school level or within the walls of our own classrooms. The power of routines is, I would hope, a widely accepted concept in teaching. It is widely understood that routines are vital in creating and maintaining school culture, directing student attention and supporting classroom management. Our colleagues at Bradford Research School have written a series of excellent blogs on the role of routines so I don’t intend to rehash old ground. But I have had a recurring question going around in my head the last few weeks:

- If the importance of routines is so mutually understood, and in many cases seemingly simple to implement, then why can they be so hard to do so across a school or just within some classrooms?

I suppose the simple answer is that routine establishment is not that simple – but that still begs the question as to why? There may be several answers, but I wonder if one major one is teacher self-efficacy.

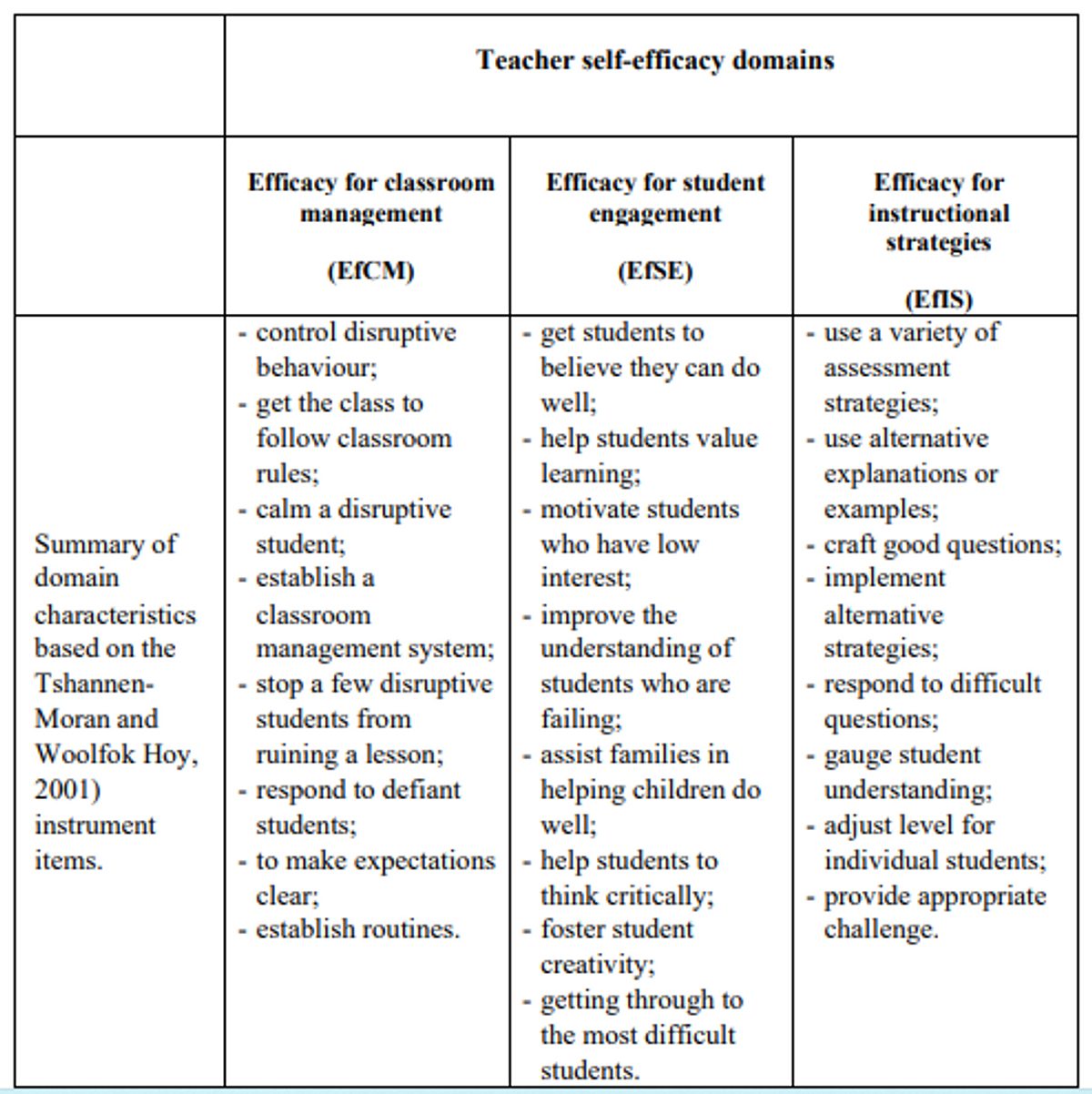

Self-efficacy refers to one’s own beliefs in our ability to achieve directed goals. Without strong self-efficacy people do not expend their efforts in endeavours because they perceive that their efforts will be futile. Tschannen-Moran and Woolfolk-Hoy (2001) divide teacher self-efficacy into 3 domains – efficacy for instructional strategies, efficacy for student engagement and efficacy for classroom management. It is under this final domain that establishing routines is classified.

Teachers self-efficacy for classroom management, defined as teacher’s judgement of their capability to successfully perform classroom management tasks such as establishing routines, is regarded as a core component of teacher competence – with multiple studies finding that teachers who feel confident in their abilities to manage classrooms report fewer disturbances. Importantly studies have also found that efficacy for classroom management was often established during teacher education and formative teaching years and then remains relatively stable until mid-career. Therefore, teachers who early on develop positive self-efficacy for classroom management are likely to find establishing routines and behaviour strategies much easier than those teachers who do not have such positive self-efficacy.

In fact, the nature of behaviour influences self-efficacy by forming a self-reinforcing cycle of either success or failure (i.e. poor behaviour/struggle to implement routines will serve to further reduce self-efficacy) and this cycle is hard to break without significant action.

What are the implications of this for schools?

The theory of self-efficacy for classroom management suggests that if staff have developed a low self-efficacy then simply knowing the benefits of implementing a new strategy (i.e. entry and exit routines) is unlikely to be enough to see the strategy become embedded. Teachers with low self-efficacy may believe themselves incapable of implementing a routine, which to staff with high self-efficacy seems relatively straightforward. In addition to this, when implementing a new approach there is often a dip in self-efficacy for all teachers, no matter their efficacy starting point, as they experience challenges in the early stages of change.

So, if school leaders want to embed classroom routines in every classroom with all staff then they need to know their staff with low self-efficacy, plan how to support them and plan for the early stage dip.

In regards to what schools can control teacher self-efficacy can be influenced through:

- Verbal Persuasion – verbal input from colleagues/supervisors that strengthens beliefs in one’s capabilities. Alone this is often not powerful enough to enforce real efficacy change but in conjunction with other strategies can be successful.

- Vicarious Experiences – observing another person complete the action – this can be done live or through a video.

- Mastery Experiences – considered to be the most influential source of efficacy; this involves personal experiences of attempting the task with success in authentic setting (i.e. the teachers own classroom).

As such if we want to develop self-efficacy we need to plan:

- How and when we are going to provide verbal persuasion? How we will make this high profile and influential?

- How we can provide models of the intended change/routine we want to establish?

- How we can ensure that teachers get a chance to practice/rehearse the strategy in authentic settings (i.e. their classroom with and without students) and then receive follow up support on how this went and where to go next?

It may just be me but the instructional coaching model would seem to fit these needs quite well.

Ben Crockett is an Assistant Head at Durrington High School. He is also Assistant Director of Durrington Research School and will be delivering training on “Feedback to Improve Learning”

Further Reading:

Watson, Steven, and Gosia Marschall. “How a trainee mathematics teacher develops teacher self-efficacy.” Teacher Development 23.4 (2019): 469 – 487.

Tschannen-Moran, Megan, and Peggy McMaster. “Sources of self-efficacy: Four professional development formats and their relationship to self-efficacy and implementation of a new teaching strategy.” The elementary school journal 110.2 (2009): 228 – 245.

More from the Durrington Research School

Show all news

The Evidence Base behind Attendance Interventions

The importance of attendance means that there is a growing demand for a review of the research into attendance interventions.

Metacognition and self-regulation in geography

Head of geography Sam Atkins explains how he has been helping students develop their metacognitive regulation .