Blog -

Improving Feedback by Improving Subject Knowledge

Investing in Subject Knowledge has Multiple Benefits

Share on:

by Bradford Research School

on the

Much of what occurs in successful school cultures and classrooms is invisible. More often than not, when observing a highly effective teacher or simply witnessing a calm transition between lessons, there is an innate feeling that something exceptional is occurring in the atmosphere of the classroom or corridor. However, it is often difficult to pinpoint what is being done for this to occur. Underneath nearly every action in an effective lesson or purposeful management of unstructured time is one key ingredient, guaranteed: routine.

Routines (or, as cited in other fields such as health, business and sport – habits) are actions triggered automatically in response to contextual clues associated with their performance. In other words, we wash our hands (routine / habit) following using the toilet (contextual clue). I should hope, at least. In our schools, routines offer an incredible value for learning.

Our job in this first post in a series focusing on routines in education is to outline what might constitute a routine in a school and elaborate on the underpinning rationale as to its existence. This will allow us, later down the line, to explore how to form and sustain effective routines as well as evaluate the effectiveness of existing routines in order to avoid lethal mutations or stagnation in school culture.

What might a routine look like in school culture?

Routines can be roughly divided into two aspects of our schools: Instructional routines (classroom teaching) and behavioural routines (culture and social norms). We must, however, acknowledge that the relationship between instruction and culture is symbiotic. Without one, the other suffers. The ideal, then, is to place value equally into both instructional and behavioural routine in order to maximise learning. For example, a well-executed classroom routine involving the handing out of a worksheet would be undermined by the absence of a behavioural routine such as students getting out of their seats or shouting out, contradicting the efficiency of the instructional routine in the first place.

In order to illustrate what routines may already exist in your school, consider what students are expected to do repeatedly, every lesson or every day. At my school, Dixons Trinity Chapeltown, we expect students to walk down corridors on the left, in silence. This is a crucial behavioural artefact of our school culture that is never deviated from. It is automatic, default and it occurs during every lesson transition, every single day. It is routine. In every single classroom you will see two mini whiteboards per desk, placed in identical fashion from one classroom to the next. Teachers, whether it is in a science lab or a French lesson, orchestrate the same instructional routine for students to complete: a clear countdown is issued; students are expected to hover their board with two hands; teachers use the phrase ‘show me’ and students flip their whiteboard, allowing the teacher to scan and check for understanding. What makes this most effective is the relationship between behaviour and instruction: The same language is used in every classroom in order to prompt non-compliance: ‘just waiting on one.’ The underpinning behavioural routine enables high quality teaching to occur – in this case, the efficient checking for student understanding of a particular task.

Why, then, are routines so effective? Why do routines support effective school culture and instruction? In essence:

When we are immersed in routine, we think less about what we are having to decide on (I should hope that following use of the toilet we don’t face a taxing decision whether or not to wash our hands – we just do it, without thought). In a classroom, this means students are not embroiled in whether or not to gossip about the weekend’s football for the first three minutes of a lesson but, instead, through habit, pick up their mini whiteboard and start writing answers to questions that are on the board because this is simply what they do, in every lesson, every day.

Let’s revisit my earlier illustration of a silent corridor and reverse the scenario. Without this behavioural routine, corridors are incredibly stimulating places. Students are faced with decisions that occupy their minds: Who should I walk with? Should I take the long route with friend x? How loud can I be? I could shout to my friend down the corridor. Year 10 students always barge past me and swear. I’m not a fan of French so I’ll come in talking to my friend and delay getting on with work.

By the time students are in their seats they are having to recover from the cognitive stimulation of the transition, delaying their ability to engage with actual learning. With a routine in place, this cognitive load is stripped away – the unnecessary and unhelpful load is taken away from them by the routine. Their attention is redeployed on what we want it to be on most: learning and acquiring knowledge.

When a behavioural routine like this is at its most effective, it becomes a cultural norm – it would be unusual for a student to decide to do anything other than walk silently to their next lesson because it is routine for everyone. Ask a student at Dixons Trinity Chapeltown why we have silent corridors and they’ll give the same response: so that when lessons are going on we do not disturb them. Or: So we waste no learning time.

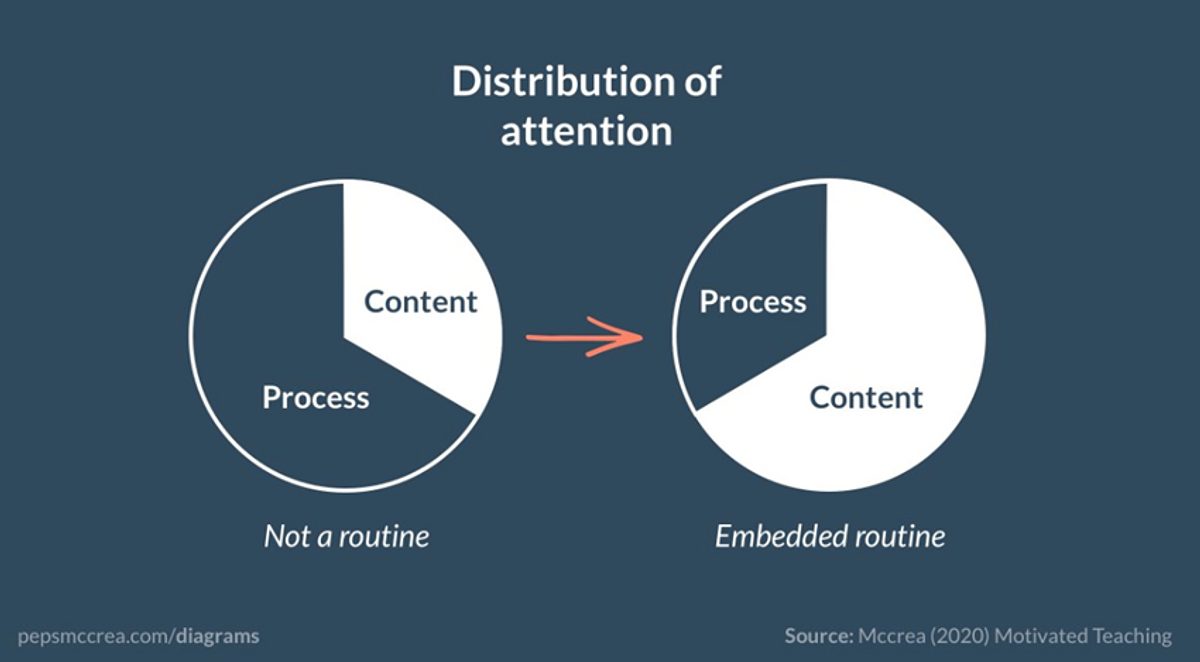

Consider the potential power of instructional routines in a lesson, where the most learning occurs. The fewer instructions a teacher has to give because a routine is a given, the more headspace they have to explain and deliver difficult content. Teaching is complex enough without extraneous instructional direction getting in the way.Peps McCrea illustrates this well through his ‘distribution of attention’ model:

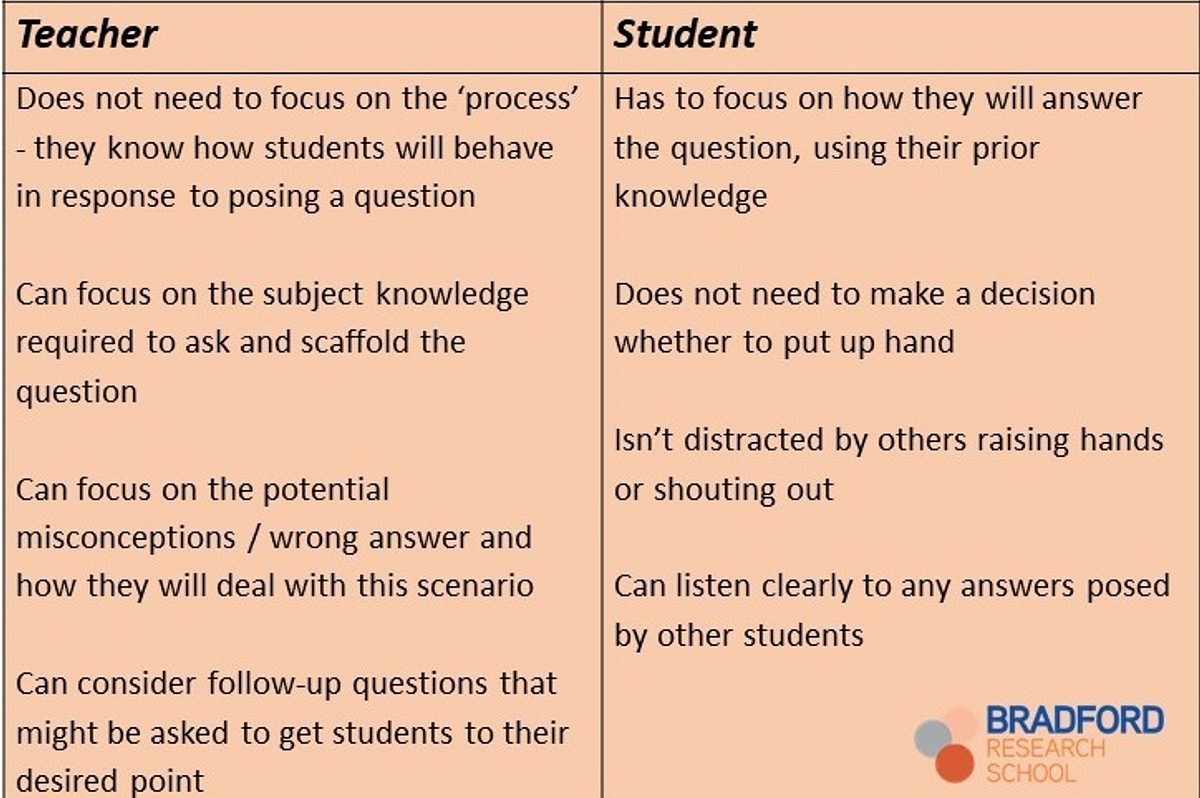

Let’s apply the concept of ‘Cold Call’, an instructional routine used across many schools, including my own, to this model. During Cold Call, it is an expectation that students’ hands are down when the teacher poses a question; students are chosen strategically by the teacher to answer the question, thus raising both accountability and think-ratio. Consider the power that this routine has on teacher and student thinking:

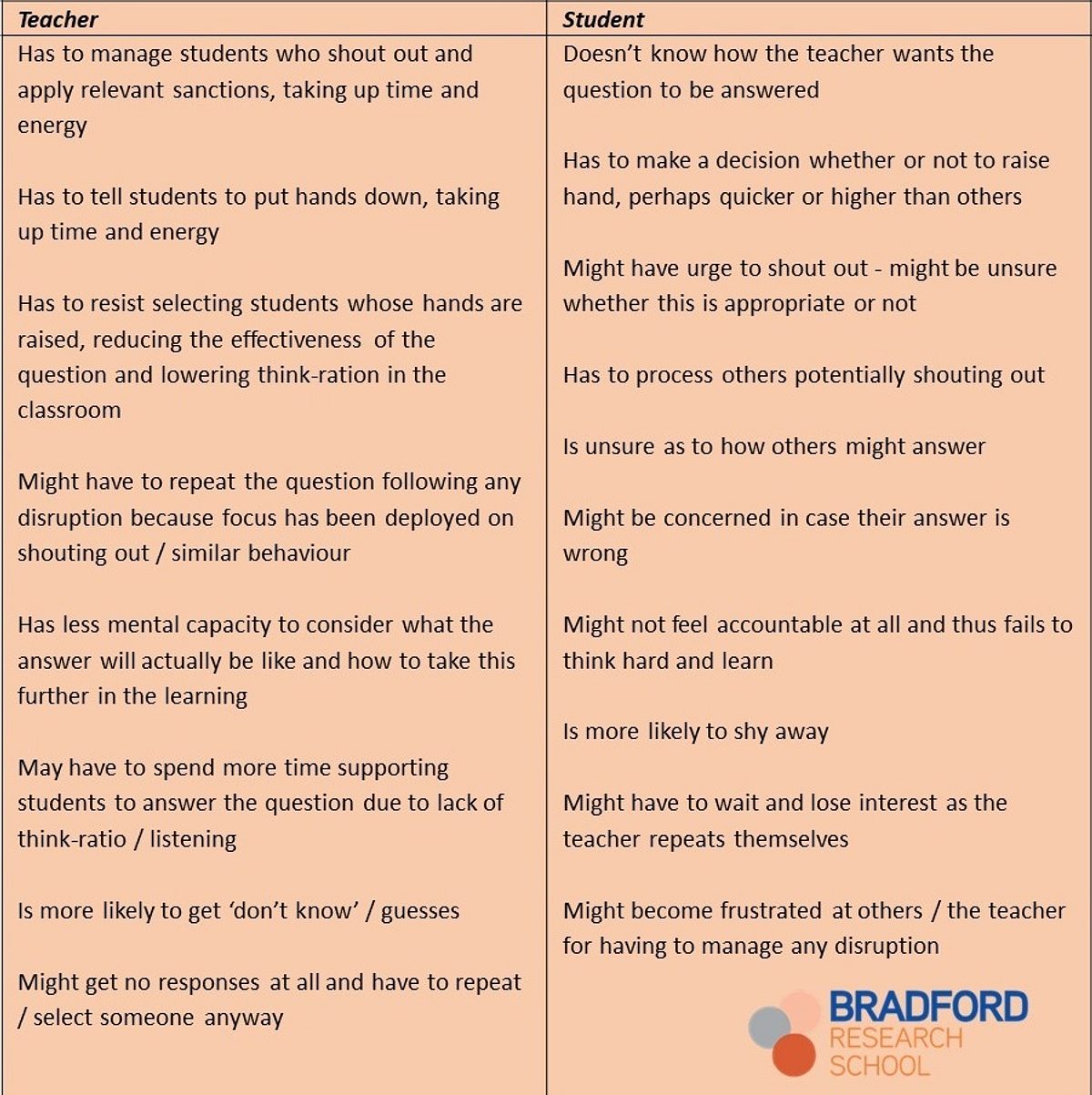

Here, as reflected in McCrea’s model, content is prioritised over process. Learning is at the heart. What happens when, without a routine, process dominates over content?

Whilst this is only one illustration, and there are many alternatives to ‘Cold Call’, it is unequivocal that the embedding of instructional routines is powerful in redeploying student attention to the challenging curriculum in front of them.

The next time, then, that you are stood in a corridor, watching students making their way to French, or the next time that you are stood in front of thirty fifteen year-olds attempting to explain equivocation in Macbeth, consider how the routines that you employ help or hinder the learning going on, day in, day out.

James Dyke is Head of English at Dixons Trinity Chapeltown. He is also an Evidence Lead for Dixons Academies Trust, focusing on the evidence around effective routines.

Blog -

Investing in Subject Knowledge has Multiple Benefits

Blog -

Success is an important factor in motivation – how do we reconcile that with desirable difficulty?

Blog -

Making it easy for students to study by teaching them how

This website collects a number of cookies from its users for improving your overall experience of the site.Read more