Blog -

Behaviour – Back to Basics

Tips for going back to basics and preventing misbehaviour from happening.

Share on:

by Shotton Hall Research School

on the

One of my earliest encounters with social and emotional learning as a teacher came in the early 2010s when I removed a faded poster from the mouldy corner of my new classroom.

I was reminded of this experience when Stuart Locke, chief executive of a trust, tweeted

his shock that the Education Endowment Foundation advocated social and emotional learning (EEF, 2019b). Stuart based his argument on his own experiences as a school leader during the 2000s and a critical review of some underlying theories (Craig, 2007).

Given this, I decided to look at the evidence for SEL, unsure of what I would find.

Fantasy evidence

When thinking about how strong the evidence is for a given issue, I find it helpful first to imagine what evidence would answer our questions. Two broad questions I have about SEL:

We would ideally have multiple recent studies comparing different SEL programmes to answer these questions. These studies would be conducted to the highest standards, like the EEF’s evaluation standards (EEF, 2017, 2018). Ideally, the array of programmes compared would include currently popular programmes and those with a promising theoretical basis. These programmes would also vary in intensity to inform decisions about dosage.

Crucially, the research would look at a broad array of outcomes, including potential negative side-effects (Zhao, 2017). Such effects matter because there is an opportunity cost to any programme. These evaluations would not only look at the immediate impact but would track important outcomes through school and even better into later life. This is important given the bold claims made for SEL programmes and the plausible argument that it takes some time for the impact to feed through into academic outcomes.

The evaluations would not be limited to comparing different SEL programmes. We would even have studies comparing the most promising SEL programmes to other promising programmes such as one-to-one tuition to understand the relative cost-effectiveness of the programmes. Finally, the evaluations would provide insights into the factors influencing programme implementation (Humphrey et al., 2016b, 2016a).

Any researcher reading this may smile at my naïve optimism. Spoiler: the available evidence does not come close to this. No area of education has evidence like this. Therefore, we must make sense of incomplete evidence.

A history lesson

Before we look at the available evidence for SEL, I want to briefly trace its history based on my somewhat rapid reading of various research and policy documents.

A widely used definition of SEL is that it refers to the process through which children learn to understand and manage emotions, set and achieve positive goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain positive relationships, and make responsible decisions (EEF, 2019b).

CASEL, a US-based SEL advocacy organisation, identify five core competencies: self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making (CASEL, 2022). A challenge with the definition of SEL is that it is slippery. This can lead to what psychologists call the jingle-jangle fallacy. The jingle fallacy occurs when we assume that two things are the same because they have the same names; the jangle fallacy occurs when two almost identical things are taken to be different because they have different names.

Interest in social and emotional learning has a long history, both in academic research and in the working lives of teachers who recognise that their responsibilities extend beyond ensuring that every pupil learns to read and write. In England, the last significant investment in social and emotional learning happened in the late 2000s and was led by Jean Gross CBE (DfE, 2007). By 2010, around 90% of primary schools and 70% of secondary schools used the approach (Humphrey et al., 2010). The programme was called the social and emotional aspects of learning (SEAL) and focused on five dimensions different from those identified by CASEL but with significant overlap.

In 2010, the DfE published an evaluation of the SEAL programme (Humphrey et al., 2010). Unfortunately, the evaluation design was not suitable to make strong claims about the programme’s impact. Before this evaluation, there were five other evaluations of the SEAL programme, including one by Ofsted (2007), which helped to pilot the approach.

In 2010, the coalition government came to power, and the national strategies stopped. Nonetheless, the interest in social and emotional learning arguably remains as a 2019 survey of primary school leaders found that it remained a very high priority for them. However, there were reasonable concerns about the representativeness of the respondents (Wigelsworth, Eccles, et al., 2020).

In the past decade, organisations interested in evidence-based policy have published reports concerning social and emotional learning. Here are twelve.

The evidence

To make sense of this array of evidence, we need to group it. There are many ways to do this, but I want to focus on three: theory, associations, and experiments.

Theory

Theory is perhaps the most complicated. To save my own embarrassment, I will simply point out that social and emotional learning programmes have diverse theoretical underpinnings, and these have varying levels of evidential support. Some are – to use a technical term – a bit whacky, while others are more compelling. A helpful review of some of the theory, particularly comparing different programmes, comes from an EEF commissioned review (Wigelsworth, Verity, et al., 2020). I also recommend this more polemical piece (Craig, 2007).

Associations

The next group of studies are those that look for associations or correlations. These studies come in many different flavours, including cohort studies that follow a group of people throughout their lives like the Millennium Cohort Study (EIF, 2015). The studies are united in that they look for patterns between SEL and other outcomes. Still, they share a common limitation: it is hard to identify what causes what. These studies can highlight areas for further investigation, but we should not attach too much weight to them. Obligatory XKCD reference.

Experiments

Experiments can test causal claims by estimating what would have happened without the intervention and comparing this to what we observe. Experiments are fundamental to science, as many things seem promising when we look at just theory and associations, but when investigated through rigorous experiments are found not to work (Goldacre, 2015).

There are four recent meta-analyses, which have included experiments (Mahoney et al., 2018). These meta-analyses have been influential in the findings from most of the reports listed above. The strength of meta-analysis, when based on a systematic review, is that it reduces the risk of bias from cherry-picking the evidence (Torgerson et al., 2017). It also allows us to combine lots of small studies, which may individually be too small to detect important effects. Plus, high-quality meta-analysis can help make sense of the variation between studies by identifying factors associated with these differences. To be clear, these are just associations, so they need to be interpreted very cautiously, but they can provide important insights for future research and practitioners interested in best bets.

Unfortunately, the meta-analyses include some pretty rubbish studies. This is a problem because the claims from some of these studies may be wrong. False. Incorrect. Mistaken. Researchers disagree on the best way of dealing with studies of varying quality. At the risk of gross oversimplification, some let almost anything in (Hattie, 2008), others apply stringent criteria and end up with few studies to review (Slavin, 1986), while others set minimum standards, but then try to take account of research quality within the analysis (Higgins, 2016).

If you looked at the eleven reports highlighted above and the rosy picture they paint, you would be forgiven for thinking that there must be a lot of evidence concerning SEL. Indeed, there is quite a lot of evidence, but the problem is that it is not all very good. Take one of the most widely cited programmes, PATHS, for which a recent focused review by the What Works Clearinghouse (think US-based EEF) found 35 studies of which:

Using the two studies that did meet the standards, the reviewers concluded that PATHS had no discernible effects on academic achievement, student social interaction, observed individual behaviour, or student emotional status (WWC, 2021).

Unpacking the Toolkit

To get into the detail, I have looked closely at just the nine studies included in the EEF’s Toolkit strand on SEL with primary aged children since 2010 (EEF, 2021). The date range is arbitrary, but I have picked the most recent studies because they are likely the best and most relevant – the Toolkit also contains studies from before 2010 and studies with older pupils. I chose primary because the EEF’s guidance report focuses on primary too. Note sampling studies from the Toolkit like this avoids bias since the Toolkit itself is based on systematic searches.

The forest plot below summarises the effects from the included studies. The evidence looks broadly positive because most of the boxes are to the right of the red line. Note that multiple effects were reported in two studies hence 11 effects, but nine studies for review.

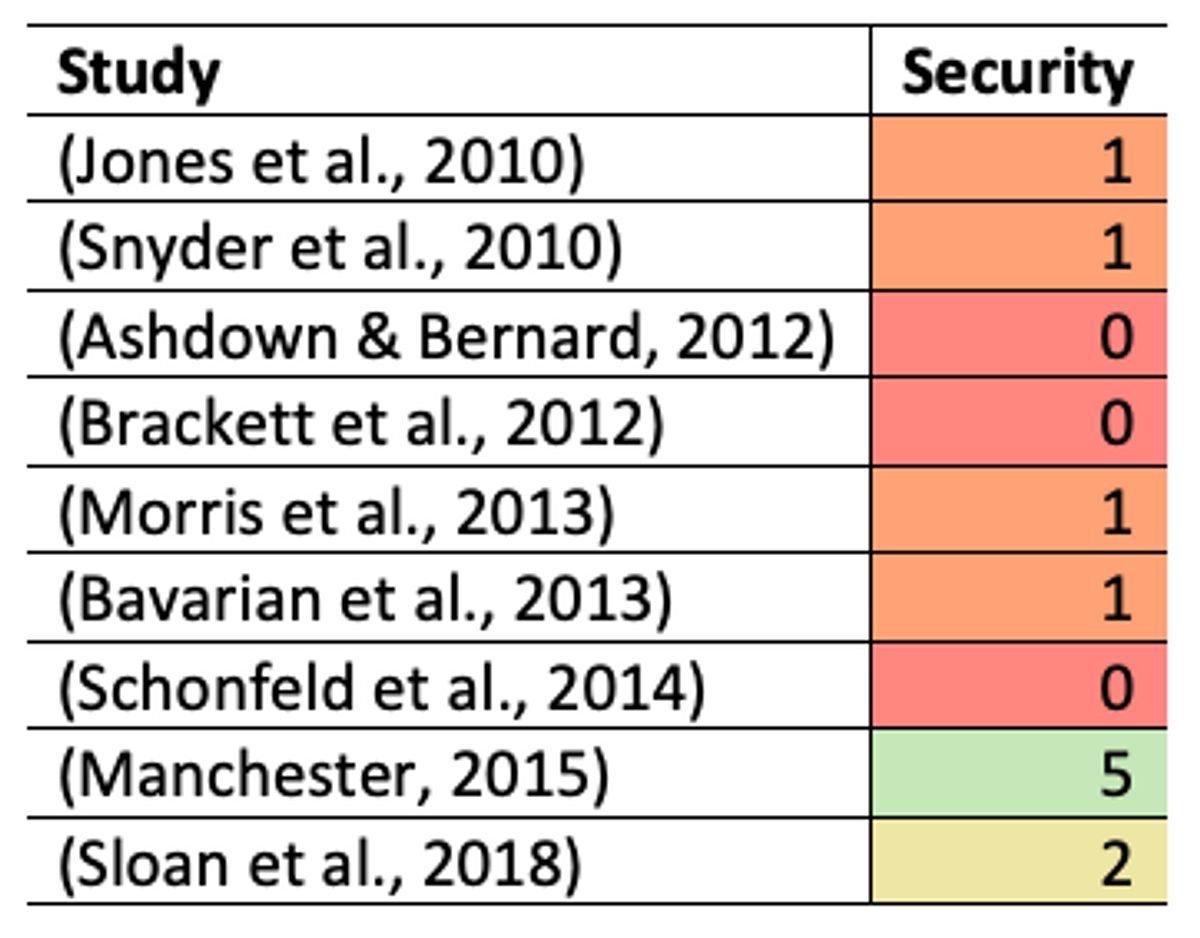

It is always tempting to begin to make sense of studies by looking at the impact, as we just did. But I hope to convince you we should start by looking at the methods. The EEF communicates the security of a finding through padlocks on a scale from 0 – 5, with five padlocks being the most secure (EEF, 2019a). Of the nine studies, two are EEF-funded studies, but for the remaining seven, I have estimated the padlocks using the EEF’s criteria.

Except for the two EEF-funded studies, the studies got either zero or one padlock. The Manchester (2015) study received the highest security rating and is a very good study: we can have high confidence in the conclusion. The Sloan (2018) study got just two padlocks but is quite compelling, all things considered. Despite being a fairly weak study by the EEF’s standards, it is still far better than the other studies.

The limitations of the remaining studies are diverse, but recurring themes include:

The SEL guidance report

Stuart’s focus was originally drawn to the Improving Social and Emotional Learning in Primary Schools guidance report (EEF, 2019b). A plank of the evidence base for this guidance report was the EEF’s Teaching and Learning Toolkit. At the time, the toolkit rated the strand as having moderate impact for moderate cost, based on extensive evidence (EEF, 2019b). Since the major relaunch of the Toolkit in 2021, the estimated cost and impact for the SEL strand have remained the same, but the security was reduced to ‘very limited evidence’ (EEF, 2021). The relaunch involved looking inside the separate meta-analysis that made up the earlier Toolkit and getting a better handle on the individual studies (TES, 2021). In the case of the SEL strand, it appears to have highlighted the relative weakness of the underlying studies.

Being evidence-informed is not about always being right. It is about making the best possible decisions with the available evidence. And as the evidence changes, we change our minds. For what it is worth, my view is that given the strong interest among teachers in social and emotional learning, it is right for organisations like the EEF to help schools make sense of the evidence – even when that evidence is relatively thin.

This rapid deep dive into the research about SEL, has also given me a necessary reminder that from time-to-time it is necessary to go back to original sources. For instance, the EEF’s recent cognitive science review found just four studies focusing on retrieval practice that received an overall rating of high (Perry et al., 2021).

Final thought

I’ll give the final word to medical statistician Professor Doug Altman: we need less research, better research, and research done for the right reasons (Altman, 1994).

References

Blog -

Tips for going back to basics and preventing misbehaviour from happening.

Blog -

Leading reading in secondary is one of the trickiest – yet most important – jobs in school. Read on for useful tips!

Blog -

Alicia McKenna, Director of Research and Training takes a look at the meteoric rise of this North East comprehensive school.

This website collects a number of cookies from its users for improving your overall experience of the site.Read more