Blog -

Behaviour – Back to Basics

Tips for going back to basics and preventing misbehaviour from happening.

Share on:

by Shotton Hall Research School

on the

As we return to school, getting the basics right is important. Like many teachers, Emily Perrin uses fact recall to settle classes and improve long-term retrieval of facts. Here she discusses how to make the most of this approach and avoid common pitfalls.

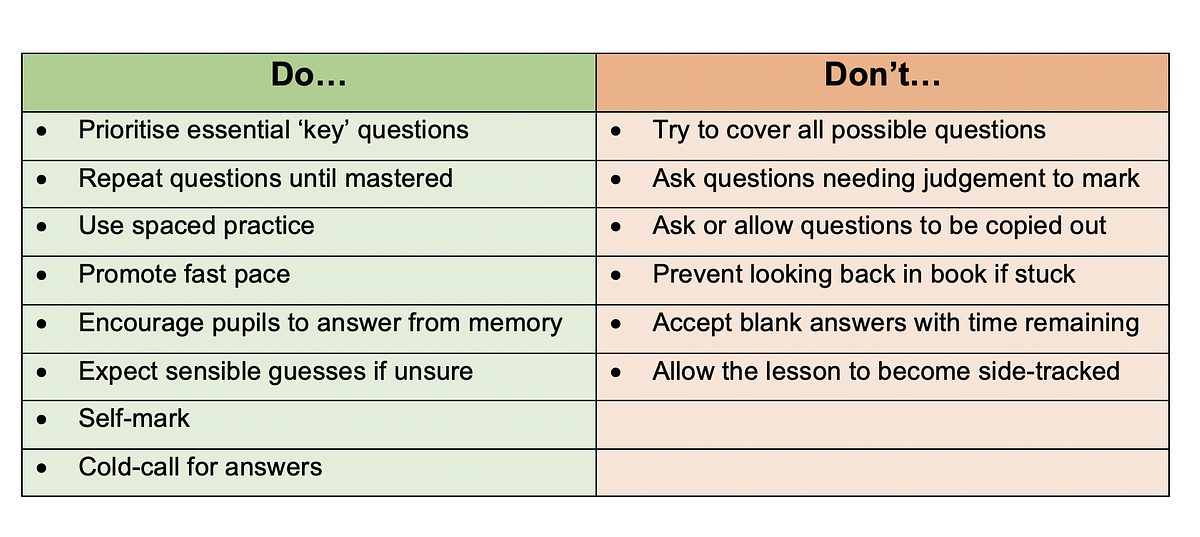

This started out as a short blog about retrieval practice… It kept getting longer so I have created a ‘too long; didn’t read’ for squeezing regular retrieval quizzes into lessons.

Memory is strengthened by practising the process of retrieving information from our long-term memory into our working memory. There is a considerable and growing body of research to support the use of retrieval practice, and more attention is being paid to the effectiveness of different forms that it may take within the classroom.

Despite being one of ‘the oldest tricks in the book’, retrieval practice has recently become something of a buzzword, and whilst it is by no means the only strategy to be employed, it does deserve the careful consideration granted to it.

Retrieval is not only effective for fact recall, but also for higher-order questions. However, in a fact-heavy subject such as my own, science, without fluent factual recall exam papers become inaccessible. This is true for all students, but allocating precious lesson time to improve retrieval is perhaps most helpful for lower attaining students.

Their weaker recall skills and typically more limited working memory hinder access to trickier questions but retrieval practice can substantially reduce this barrier. Teachers often struggle to instil independent revision habits with these pupils, and so arguably retrieval practice within lessons is even more important.

However, that’s not to say it’s not worth the effort with higher attaining classes, too. The process can be quicker, so the slightly lower benefit is still worthwhile. As a further benefit, regular retrieval practice within lessons is appreciated by pupils and reduces test anxiety.

Regular quizzing is an effective form of retrieval practice; it can be integrated simply and effectively into every lesson by way of a quick quiz as a ‘starter’. This has been done by many teachers for many years, and is in line with Rosenshine’s increasingly popular ‘Principles of Instruction’, but there are some caveats to consider.

To implement effective change in lessons it is important to identify what, precisely, needs to improve.

When ‘defining the problem’ within my own biology classes I identified limited working memory, test anxiety and – above all – poor fact recall, which limited access to higher order questions. Retrieval practice to improve fast recall of key facts could provide a clear solution here, but the solution needs to be carefully matched to the problem. Practising fact recall does not necessarily improve higher order responses, for example, but is essential for success within my context, so I chose to integrate fact recall quizzes into the beginning of every lesson.

The most important knowledge needs prioritising. There are hundreds of facts to be learnt, but some are more ‘key’ than others. In biology, for example, recalling the fundamentals of diffusion is crucial for many higher order questions – recounting the definition is also a very common exam question, whereas symptoms of tobacco mosaic virus infection is both a less common question and does not increase access to others.

My aim is to retrieve important key facts very well, not to attempt the impossible and cover every possible question with no time to consolidate retrieval. I’ve found my ‘sweet spot’ is 7 questions answered and marked within the first 10 minutes of the lesson bell – more than this is too long. Three questions from the last lesson or current topic, two or three from a recent topic and two or three from older topics is a simple way to integrate interleaving and spaced learning. It is particularly helpful to pick questions from past learning that are central to their current learning, e.g. ‘what’s the role of the mitochondria?’ from KS3 for a GCSE lesson on respiration.

Including a mixture of easier and harder questions – tailored to the class – is effective in developing confidence. Without sufficient challenge, the benefits will be muted. However, it can be tempting to avoid questions that you know pupils can answer well; this makes the dangerous assumption that these facts do not need to be practised. They do, and should reappear periodically to support fast and efficient recall.

Questions that were poorly answered should reappear until correctly answered by the majority, with the spacing between their reappearance then increased. For this reason, I write the next lesson’s questions for a class after each lesson, to ensure that they are tailored to the needs of that particular class – this is two minutes of my time well spent.

One of the biggest concerns we have with integrating ‘more stuff’ into lessons is timing pressures, something I’m very conscious of myself, so I take steps to maximise effectiveness for minimum time and effort.

My aim is not to produce work in exercise books that can be used for revision; it is the process, not the output, that holds the benefits, and so the quality of the process should be the focus.

I do not allow pupils to waste time copying out questions or writing in full sentences; the time involved in this is not worth the tiny benefit. Filling in one-word answers when marking can be a reasonable compromise, as it allows a record of what pupils did not know about.

Clarity of purpose is crucial. My aim is typically to improve fact recall, and as such this is not typically the time for ‘explain’ questions, which take too long to answer, and their marking is more open to interpretation too, defeating the aims of the exercise. An exception would be where there is one short ‘key term’ answer I want pupils to remember. For example, ‘how do thin alveolar walls speed up diffusion?’

‘Short diffusion pathway’.

I prefer other forms of retrieval for higher order questions throughout the lesson; whilst quiz starters are effective, they should by no means be the only

form of retrieval practice within the arsenal.

Questions are clear and concise to support a fast pace and reduce wasted time. I aim for a one-word answer whenever possible, with no more than one longer or perhaps two short definitions to be written.

When pupils are answering questions, it is essential they try from memory – without this, it’s not retrieval practice!

If pupils cannot come up with an answer they then look back in their book, and I offer further prompts to struggling individuals. Questions from further back in their learning present higher levels of challenge, and so may require more scaffolding or multiple-choice options.

I have a strictly followed rule of ‘sensible guess’ with no blanks left, to encourage resilience and reduce ‘failure avoidance’; even incorrect guesses can lead to effective learning of the correct answer (perhaps even more so). This is further aided by the process being very low stakes; there’s no revision of topics, pass mark or collection of scores, because my expectation is engagement with the process, which is more valuable than the outcome.

Self-marking allows efficient, instant feedback. For this to work, answers should not be open to interpretation; they should very clearly be right or wrong, and ideally just one word.

Definitions should be a very clear phrase, with essential wording made clear. For example, pathogen = microorganism that causes disease.

‘Cold calling’ saves time and can promote engagement. It can also develop pupils’ confidence if I know they have a correct answer. This marking time can be used to address minor misconceptions, but I think it is crucial to avoid becoming side-tracked. Larger issues should be noted and then addressed at an appropriate point within the scheme of learning.

Aside from a huge improvement in pupil recall of key facts, and their subsequent access to higher-order questioning, I’ve noticed a multitude of other benefits in my lessons over the last couple of years that I’ve been doing this.

Students understand the aims of the process, can clearly see an improvement in their recall and take pride in this, relishing the challenge with more difficult questions and steadily improving in confidence. Despite a few teething problems, all my classes are now accustomed to and engaged with the process. It has instilled good habits within my classes, working well as a settling activity, and is perhaps my most valuable routine.

Here are some questions I recently used for retrieval practice.

Blog -

Tips for going back to basics and preventing misbehaviour from happening.

Blog -

Leading reading in secondary is one of the trickiest – yet most important – jobs in school. Read on for useful tips!

Blog -

Alicia McKenna, Director of Research and Training takes a look at the meteoric rise of this North East comprehensive school.

This website collects a number of cookies from its users for improving your overall experience of the site.Read more