Secondary Case study: student leadership of extracurricular clubs

Utilising sixth formers to boost the extracurricular offer

Share on:

by Huntington Research School

on the

As we prepare for children to return to school, many of our thoughts will be on how we can support pupils who have missed out on months of classroom teaching as a result of partial school closures.

As we consider the options available to us it is important to acknowledge the importance of supporting effective implementation in any change in practice or additional provision we provide. As Professor Jonathan Sharples, a professional research fellow at the EEF said in his 2019blog, “Effective implementation, for us, has always been about making, as well as acting on, evidence informed decisions”.

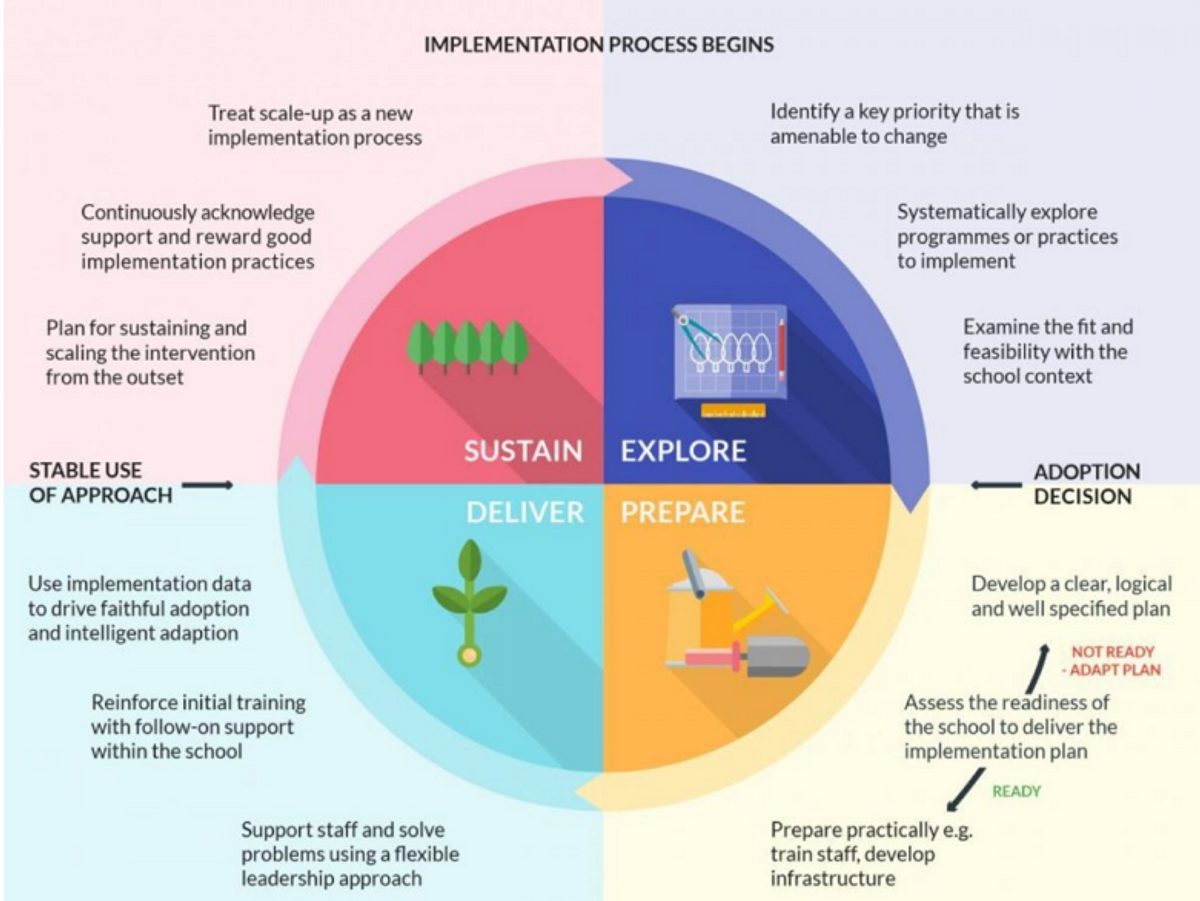

In 2018, the EEF released ‘A School’s Guide to Implementation’, which aims to support schools to ‘develop a better understanding of how to make changes to practice by offering practical and evidence-informed recommendations for effective implementation’. An overview of the implementation process is outlined below:

A key focus of this guide is the need to undertake thorough exploration of your issue. This section of the guidance report was updated in December 2019 and now includes more detail on defining the problem you want to solve and identifying appropriate programmes or practices to implement. This provides two distinctly different parts to the exploration phase:

1. Exploring the issue – identifying one or a small number of improvement priorities

2. Exploring possible solutions – making evidence-informed decisions on what to implement

This blog is the first of two parts looking at how when children return to school we should look to identify a tight area for improvement using a robust diagnostic process.

Rather than making predictions and assumptions about what we think children have missed it will be important for us to use diagnostic assessment in order to clearly identify what children do and do not know and understand, and can and cannot do.

We need to think carefully about the type of assessment we use and whether it is going to provide us with valid data on our issue. For example, if a student is unable to answer a mathematics question is this because they lack the mathematical knowledge, they don’t know or remember the procedure, or is it actually a vocabulary issue where they don’t understand the language used in the question? Furthermore, could it be an issue with motivation or lack of engagement with learning?

The NFER report ‘School’s responses to Covid-19’ surveyed over 3,000 school leaders and teachers and found that:

- Teachers report covering, on average, only 66% of the usual curriculum during the 2019 – 20 school year

- Teachers estimate that their pupils are three months behind, on average.

- 61% of teachers report that the learning gap between disadvantaged pupils and their peers has widened since the previous year

Other research also suggests that disadvantaged pupils are more likely to be have been negatively affected by the pandemic: the Institute for Fiscal Studies interviewed over 5500 parents and found that, while the COVID-19 crisis has affected all families with children, it has not affected them all equally. We need to ensure that we explore and understand how they have been affected whilst remembering that not all students (including disadvantaged students) will have been affected in the same way.

The unprecedented nature of the current crisis makes it hard to predict the actual effects that it has had. However, it is likely that the development of early language and communication and particularly mathematics and early reading will have been affected. Indeed, the Best evidence on impact of school closures on the attainment gap interim report published in January 2021 found that ‘primary-age pupils have significantly lower achievement in both reading and maths as a likely result of missed learning. In addition, there is a large and concerning attainment gap between disadvantaged pupils and non-disadvantaged pupils.

Using assessment to explore and identify gaps in knowledge will be important as secure background knowledge forms the best foundation for building new learning and developing a pupil’s schema. It is also highly likely that pupil’s metacognitive skills will be less well developed because of the lack of school experience. Supporting self-efficacy and supporting pupils to manage their motivation so that they can direct and purposefully monitor their own thinking and learning will need to go hand-in hand with any reinvigoration of knowledge.

The negative effects of the pandemic are likely to extend beyond educational attainment. Research has shown clear evidence of reductions in mental health among young people, with 27% of young women showing potential mental health problems. We will also need to explore this issue and the EEF Improving Social and Emotional Learning Guidance Report offers valuable advice about how we can integrate and model SEL skills through everyday teaching.

Julie Kettlewell and Jane Elsworth, Huntington Research School

Look out for Part 2- Exploring the solutions from Friday 5th March 2021

Utilising sixth formers to boost the extracurricular offer

Fostering Belonging and Growth through a coherent extracurricular offer

How can we refine existing literacy approaches?

This website collects a number of cookies from its users for improving your overall experience of the site.Read more