Secondary Case study: student leadership of extracurricular clubs

Utilising sixth formers to boost the extracurricular offer

Share on:

by Huntington Research School

on the

Cognitive science is currently all the rage and one theory appears to trump all others at the moment: Cognitive load theory. The theory was introduced in the 1980s by John Sweller but in 2017 it became a began to receive more widespread attention, probably helped by Dylan Wiliam tweeting:

Policymakers then recognised its importance including Ofsted and the new DfE Early Career Framework.

So what is cognitive load theory? The theory states that working memory (WM) plays an important role in the learning process. If we overload WM some information falls out so never gets transferred to Long Term Memory (LTM). CLT is based on the belief that learning is a result of changes to LTM.

In the original theory three separate types of cognitive load were identified:

Intrinsic cognitive load (manage the impact of this)

This is determined by both the complexity of the information being introduced.

Extraneous cognitive load (minimise this)

This is not determined by the intrinsic complexity of the information but rather how the information is presented, and what the learner is required to do by the instructional procedure.

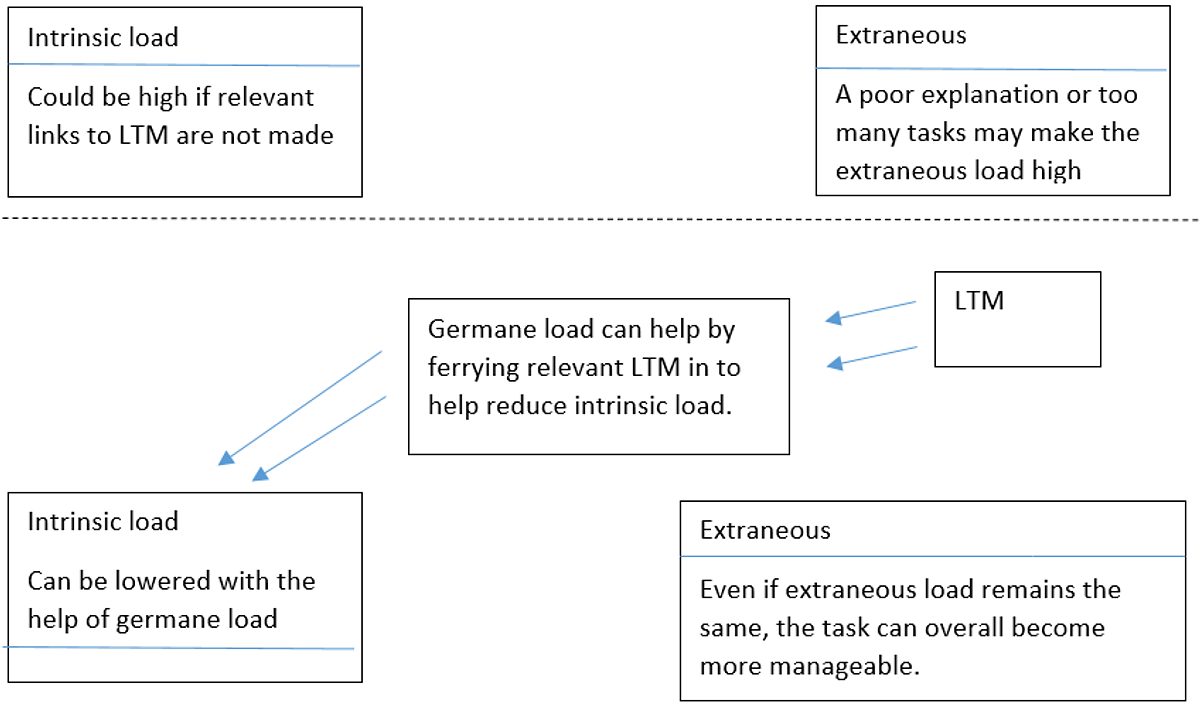

Germane cognitive load (maximise this)

The ability to make explicit links to relevant LTM information that can therefore help manage the level of intrinsic cognitive load. In that sense, intrinsic and germane cognitive load were closely intertwined (which has helped inform the amendments).

What has changed with cognitive load theory?

In January 2019 Sweller et al. released a review (‘Cognitive Architecture and Instructional Design: 20 Years Later’) where they refer to what they have learnt since the theory was originally introduced and include some important amendments to the theory.

In a move from the original model germane load is now removed as a separate source of cognitive load.

The new version of the theory assumes that rather than contributing to the total load, germane cognitive load redistributes working memory resources from extraneous activities to intrinsic activities. Picture it as an enthusiastic (and intelligent) minion who is doing its utmost to find relevant links to LTM that will enable an individual to feel that a task is more manageable because of what they already know.

The inevitable critique of cognitive load theory

As can happen when a new idea gets increased attention, comment and critique can arise. (including this recent TES article) This is a vital and useful part of the process, especially when we are thinking about applying concepts to a classroom setting. Some of the criticisms about the theory have been:

- Overemphasis on teacher led instructions rather than child-led discovery approaches.

- Social and subjective elements of the learning process are side-lined, including social-emotional development, character development and values.

- There is likely to be more to processing than just space in working memory. The role of attention is important. Distraction is more likely if content is oversimplified/under-stimulating.

- Cognitive load is not measureable. There are no specified units and no way of measuring it empirically. Measurement is often based on self-report.

- There are many reasons why a child may fail to complete a task successfully (not just limited capacity of WM). WM can be overstretched at the point of instruction, students may decide not to engage with instructions as they are not interested, lack self-esteem or don’t like the teacher.

What does this mean for teachers?

To help mitigate against extraneous load, teachers must think carefully about how information is presented and explained to pupils. They must also plan lesson content and progression carefully to ensure pupils are not asked to do too much with that new information. So if I have just started Macbeth with a class I might not want my first lesson to entail reading the first scene and beginning to discuss the contextual significance of witches. Instead I might focus the first few lessons on understanding the plot and then begin to teach about relevant contextual ideas: or vice-a-versa.

Teachers obviously have a role in helping pupils make explicit links to previous learning. It is of little surprise then that new research relates CLT to self-regulated learning and learners monitoring and controlling their learning processes. That ability for pupils to pause, think back (or look back in their book) to previous learning is a useful skill, but one that will most likely need to be explicitly modelled to them because only the most successful of learners will implicitly start making links to other learning.

Despite the criticisms and the amendments, the key point of the theory was, and remains, around ensuring teaching is at the appropriate level of challenge. This is an essential consideration and it seems logical that we should be keeping this in mind at all times in our teaching.

Julie Watson, Memory and Metacognition lead, Huntington Research School

There are now handy resources related to CLT specifically designed for teachers and other educational practitioners that are well worth a look e.g. Centre for Educational Statistics and Evaluation 2017, 2018; Clark 2014; Young et al. 2014.

Useful links

https://teachinghow2s.com/docs/Cog_Load_Theory_Poster.pdfhttp://www.ollielovell.com/pedagogy/johnsweller/https://educationinspection.blog.gov.uk/2019/02/13/developing-the-education-inspection-framework-how-we-used-cognitive-load-theory/

Utilising sixth formers to boost the extracurricular offer

Fostering Belonging and Growth through a coherent extracurricular offer

How can we refine existing literacy approaches?

This website collects a number of cookies from its users for improving your overall experience of the site.Read more