Research School Network: The Language of High Expectations Chris Runeckles discusses the importance of language in making high expectations a reality

—

The Language of High Expectations

Chris Runeckles discusses the importance of language in making high expectations a reality

Share on:

by Durrington Research School

on the

We’ve been talking a lot about high expectations in these first few days of term here at Durrington. How we set them, how we maintain them, how we communicate them.

When it comes to high expectations, the words we choose really matter. They have the capacity to either raise or lower the bar we expect our pupils to reach.

This is not just in what we say in the classroom but also how we speak to each other in offices and corridors.

When discussing how schools can truly embody high expectations of disadvantaged pupils Marc Rowland often refers to removing the deficit discourse in our schools. More specifically, that disadvantaged pupils and their families are not spoken about as a problem to be resolved but instead held in high regard as intrinsic to our school communities.

This is key, as we know we carry significant bias as teachers (whether we like to acknowledge it or not). Papers such as “She doesn’t shout at no girls” explore the effect of teacher bias, albeit connected to gender in this case. If these biases are allowed to run unchecked they can amplify the low expectations that can unfortunately follow labels such as PP and SEND.

This means we need to be conscious of the language we use when discussing our pupils and ensure we live and breathe the high expectations we all want to embody. For example, when scanning your new September class list with a colleague one response to noticing a particular pupil on the list might be:

“I’m going to struggle with XXX this year, they are really lazy.”

That sort of discourse seeps into the fabric of our thinking and will chip away at high expectations. This makes subsequent attempts to set and maintain high expectations more of a veneer than a lived reality.

Ultimately, if we don’t really believe in the high expectations we may espouse in classrooms, the ultimate impact on pupils is likely to be limited. The evidence for this stretches back more than 50 years, most famously with the much quoted Pygmalion in the classroom study from the 1960s. This study found that when teachers were told (completely falsely) that some children were “spurters” they approached teaching differently and the children rose to meet those high expectations.

Accepting the language outside of the classroom sets the foundations for high expectations, it is the language used inside the classroom that can directly change pupil behaviour.

Knowing this is one thing, but practical steps for achieving it is another. Thankfully this is something that several educational publications have attempted to articulate. In Making Every Lesson Count, the first chapter on challenge explains how we can ensure challenging lessons for all pupils, no matter their starting point. An example would be:

Set single challenging learning objectives

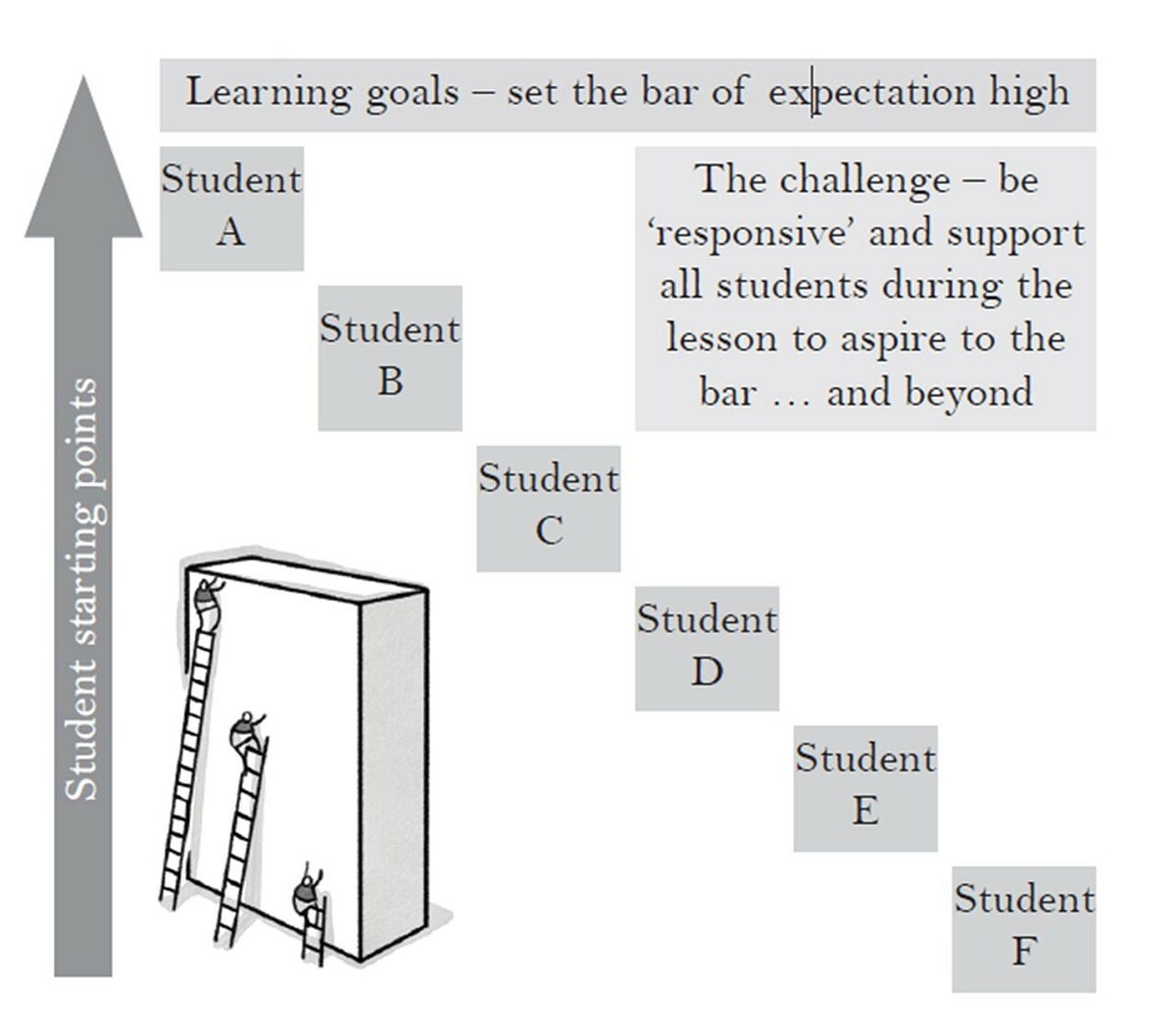

This is not about what is written or projected, but a belief that all pupils will reach the challenging objective we set for each chunk of learning. Getting to that point will be different and will require responsive teaching (as shown by the diagram below), however we must not communicate that certain chunks of learning or lessons are only applicable to high attaining pupils.

Again, language is key here. If, in a history lesson, we say to certain pupils that they should only read the shorter sources, how can we expect them to believe they are capable of meeting the same goals as the pupil sitting next to them who is asked to look at everything. Instead, through strategies such as reading text aloud to the class and explicit vocabulary instruction, we can then use the language with our pupils that no element of the lesson is ring-fenced for certain pupils.

Doug Lemov’s Teach Like a Champion also gives teachers support in the specific language to use with pupils to support teaching with high expectations. In chapter one, several strategies speak to this. One example would be:

Right is Right

This strategy is about the difference between a partially correct answer and a fully correct one. We can have a habit of “rounding-up” as teachers, accepting a partial answer and then filling in the blanks ourselves. To show really high expectations we need to tell students that they are almost there and then help them, through verbal scaffolding if necessary, to give a more complete response.

Here then, the words we use matter again, as we navigate the line of holding high expectations while maintaining a pupil’s willingness to contribute in class. The easier option is of course to make the correction and it may feel kinder in the short term. However, ultimately it leaves partial or incorrect answers unchallenged in pupil thinking.

The nuance of language is therefore also important in high expectations. A blunt tool such as starting the year telling everyone they will achieve a grade 9 is unlikely to yield results. Inner Drive recently published a blog on their site listing five ways to maximise the power of high expectations which addressed this. The third strategy was:

Balancing expectations: The Goldilocks Principle

This drew on research that unrealistic expectations can actually harm academic performance. As a result, we need to set high expectations that promote maximum challenge but remain achievable. The only way we can do this is through deep knowledge of our pupils, understanding how far we can push them and what specifically they need to do to make the leaps forward they require. We need to pitch them into the struggle zone, with maximum thinking but low stress, expecting them to grapple with what at the far edges of their capability.

Again, language plays a vital part in this. The EEF’s guidance report on feedback tells us that feedback directed at the person rather than the task is the most dangerous as it can set the wrong expectations. Telling a student that they have tried really hard when in fact they have largely coasted can lower their expectations of what is required. Instead our language must constantly push towards specific academic improvement: “The next step for you is to include more precise geographical terms in your writing.”

Teaching is great for giving us a fresh start every September. So, as we start this new year, we should be mindful of the words we use with both our colleagues and our classes and ensure they communicate the highest expectations for all.

By Chris Runeckles

More from the Durrington Research School

Show all news

The Evidence Base behind Attendance Interventions

The importance of attendance means that there is a growing demand for a review of the research into attendance interventions.

Metacognition and self-regulation in geography

Head of geography Sam Atkins explains how he has been helping students develop their metacognitive regulation .