Research School Network: Creating the Climate for Metacognitive Thinking Durrington Research School Director Chris Runeckles explores creating the classroom conditions metacognition requires

—

Creating the Climate for Metacognitive Thinking

Durrington Research School Director Chris Runeckles explores creating the classroom conditions metacognition requires

Share on:

by Durrington Research School

on the

The chief challenge surrounding successful metacognition interventions is often described as the difficulty in turning theory into practice. This is in large part due to the relative complexity of metacognition conceptually.

The EEF toolkit promises a potential 8 months extra progress for metacognitive interventions, the highest impact rating of any toolkit strand. Of course, the devil is in the detail, and these transformative benefits are only possible if the concepts underpinning metacognition are both deeply understood and interpreted in a way that brings change to teaching habits.

As a result, much of the focus of the EEF’s Metacognition and Self-Regulated Learning Guidance Report is on supporting teachers with how they can adapt and change their practice. The two areas I’ve blogged most about in the past are particularly connected to strand 3, modelling, and strand 5, metacognitive talk. You can read more about that here.

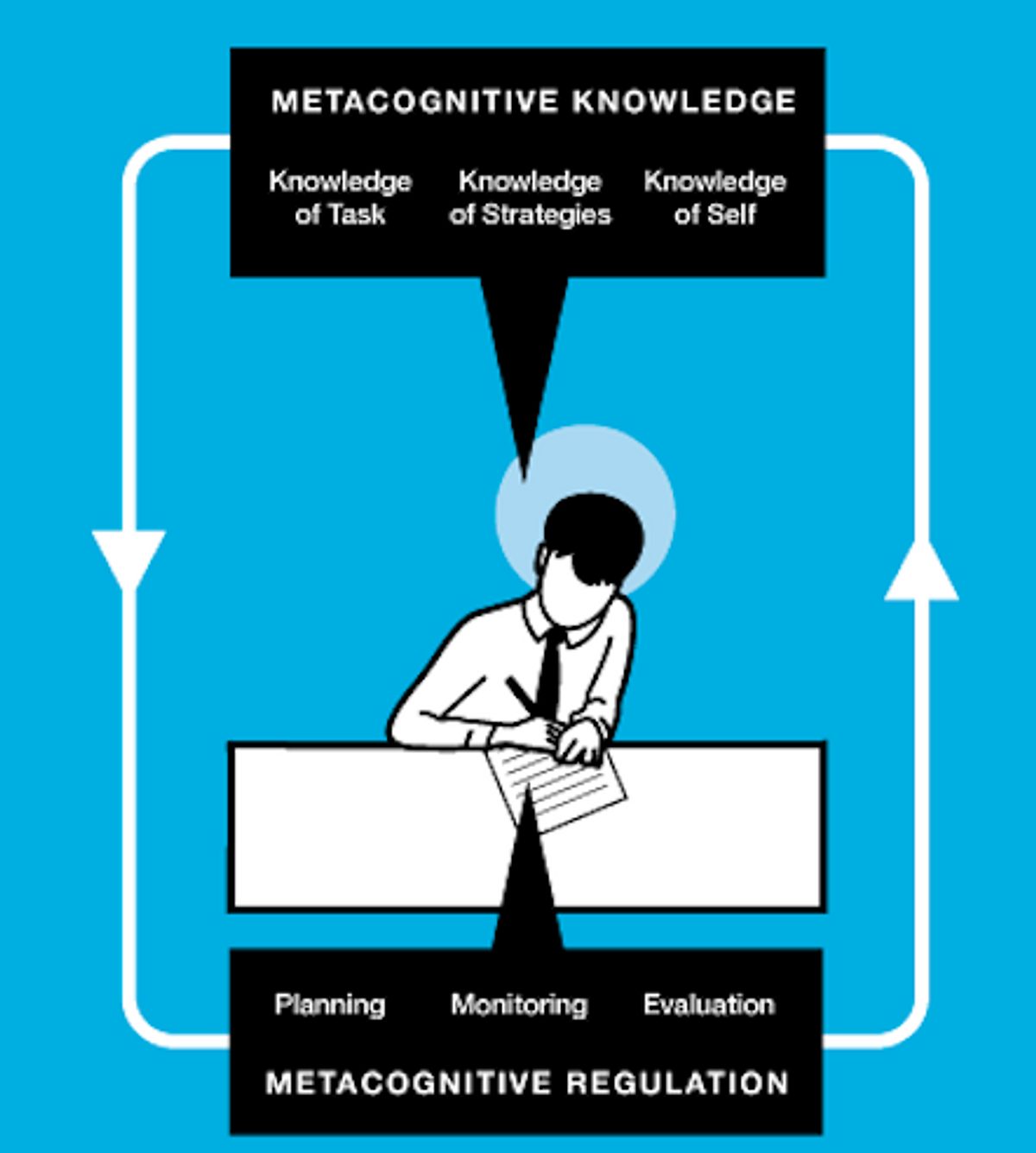

These changes to teacher practice are extremely important in bringing the theory of metacognition into classrooms and realising its substantial benefits. If we want to engender metacognitive knowledge and metacognitive regulation in the areas detailed in the image below, then we need to explicitly teach them. We need to demystify metacognitive thought, make it normal, and remove the mystique. We want to make it normal, for example, for a student to think about a range of strategies before completing a task and then consciously select the one that they believe will give them the best chance of success. This is important for all students but particularly disadvantaged students and those with SEND.

However, what sometimes gets missed in all of this is the climate required for metacognitive thinking to take place. Ultimately, metacognition and self-regulated learning is not about what teachers do, it is about how students think. This is largely hidden from us as it is the purposeful direction of thought and is therefore only on show when we make the effort to uncover it. As well as the sort of interventions detailed in the blog linked above, we also need to create a classroom climate that nurtures this type of thinking and makes it as likely as possible that students will engage with it. Here are five suggestions for how we can do that:

1. Get the challenge right

This is partly covered in the guidance report under strand 4, which is about challenge. The nutshell version of this is that when challenge is too low we are not metacognitive because there is no need to be, and when it is too high we are not metacognitive because we are too stressed and overwhelmed to think strategically. Pitching students into struggle and deliberate practice right at the edges of the capability is the sweet spot for metacognitive thought to happen.

2. Build self-efficacy

To quote Daniel Muijs (might be a paraphrasing) “The effect of achievement on self concept is greater than the effect of self-concept on achievement.” In other words students need to experience success before they believe they can succeed. The more we build the belief in students that they are going to succeed at the task at hand (their self-efficacy) then the more likely it is that they will think metacognitively about it. If they don’t believe they will succeed motivation will be low and so will purposeful thinking.

3. Reduce extraneous cognitive load

Asking students to think metacognitively is asking them to take on another layer of thought on top of the thinking they have to do to both recall the relevant knowledge and the procedural knowledge required to complete the task. Therefore we need to clear out the clutter to support that thinking. Anything that is vying for their attention, be that the teacher talking over the top of reading, busy slides or displays, or a noisy room is going to increase extraneous cognitive load and thereby inhibit thinking. Metacognition is likely to be down the list of priorities at this point and less likely to happen.

4. Provide prompts and cues

If we accept the premise that we students can learn to think metacognitively and it isn’t simply down to chance whether they do or not, then regular prompts and cues will remind them of the sorts of internal questions to be posing themselves. One way we can do this is visually, for example adding metacognitive prompt questions to powerpoint slides or worked examples. We can also intervene as teachers, asking prompt questions such as “which strategies could you use to complete this task?”

5. Lay the foundations

Self-regulated learning has three parts: cognition (your toolbox of strategies), metacognition (deploying these tools strategically and effectively), and motivation (the desire to use your tools). There is no hierarchy to these elements and all need to be present for self-regulation to take place. Therefore, we need to ensure a level playing field of cognition for our students. This means ensuring the essential knowledge has been taught and understood. This is both the declarative knowledge (i.e. what happened during the Cuban Missile Crisis) and the procedural knowledge (i.e. how to write about causation in history). Again, this is important for all, but particularly for our disadvantaged students.

All of this is not to say the explicit teaching of metacognition should take a back seat. It certainly shouldn’t, and is essential to developing the self-regulating students that we all want to see. It is more to say that developing metacognition in our classrooms needs to be seen from two perspectives: first, the lens of the teacher, how can we adapt our practice to explicitly teach metacognitive knowledge and regulation within our domains; second the lens of the student, how we can create the conditions most conducive to thinking metacognitively. If we can get both of these right then the benefits promised in the EEF toolkit will move closer to a reality.

By Chris Runeckles Director of Durrington Research School

More from the Durrington Research School

Show all news

The Evidence Base behind Attendance Interventions

The importance of attendance means that there is a growing demand for a review of the research into attendance interventions.

Metacognition and self-regulation in geography

Head of geography Sam Atkins explains how he has been helping students develop their metacognitive regulation .