Blog -

Scaffolding to Support Working Memory Demands: Questions for Reflection

We share questions and resources to unpick the EEF’s Voices from the Classroom

Share on:

by Bradford Research School

on the

School life moves at incredible pace. And this time of year is no different. New initiatives are being launched, and inboxes are flooding with the next set of school priorities.

The nature of school results and the need to feel impact are very real and understandable reasons why we want to get things done quickly. And while there are certainly problems in schools that we might want to fix quickly, one of the best things any of us who work in schools can do is simple: slow down.

It’s a message that runs through the EEF’s School’s Guide to Implementation. In fact, the word ‘time’ is mentioned on 68 occasions through the guidance. Every opportunity is taken to reiterate the need to allow the appropriate time:

There are no fixed timelines for a good implementation process; its duration will depend on the intervention itself—its complexity, adaptability, and readiness for use—and the local context into which it will be embedded. Nevertheless, it is not unusual to spend between two and four years on an implementation process for complex, whole-school initiatives.

Quick pace looks for activity; slow pace looks for the problem

It always feels better to be doing something. But sometimes this translates as we should do anything. And if we’re not careful, this anything is not the thing that should be the real focus. As they say in the guidance:

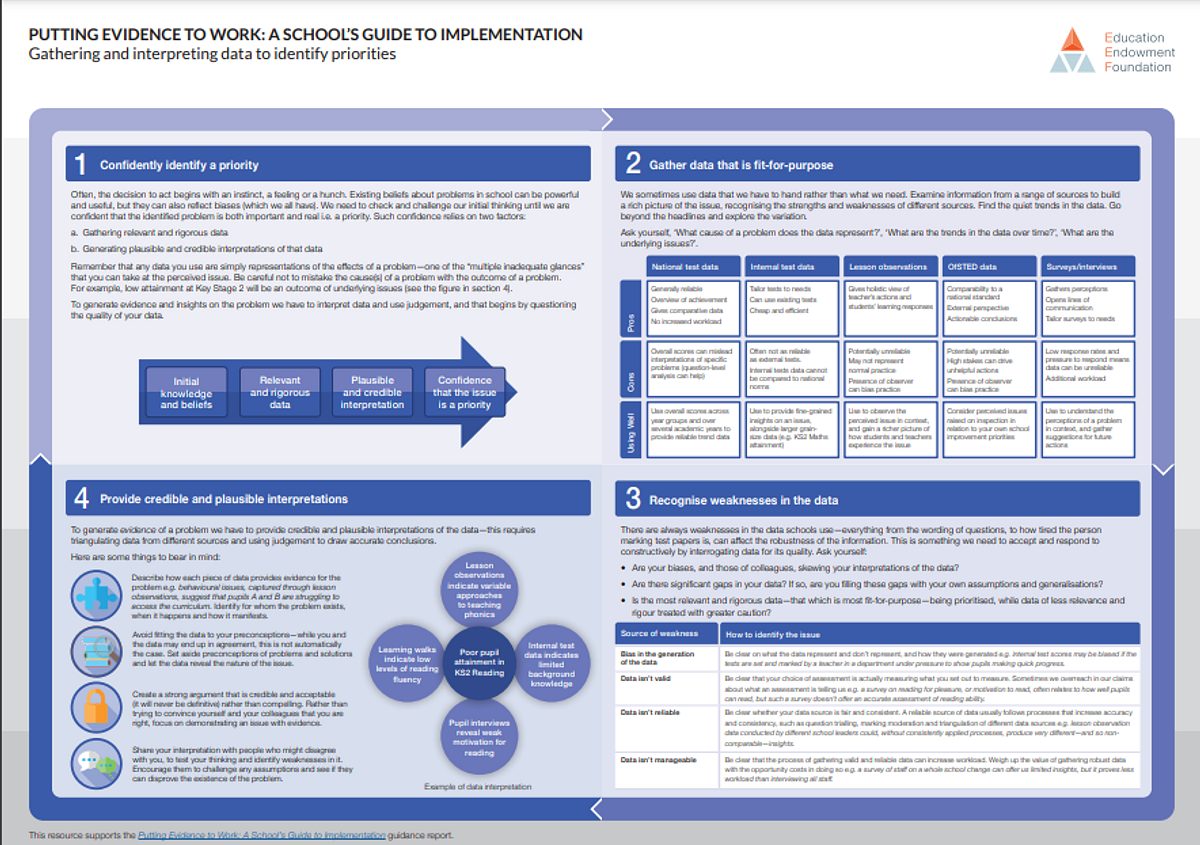

“…the first step when thinking about implementation is to identify a tight and appropriate area for improvement using a robust diagnostic process. Don’t jump to considering new approaches to implement before rigorously examining the problem — these will inevitably bias your view of the issue.”

There is a great section in the guidance to help, which is also available as a poster.

Going through the process helps to ensure that what you are doing is the right thing. And maybe it is the same thing that you were going to do in the first place, but the process will still ensure that there is a clear and convincing rationale, and theory of change that will help sustain the intervention for the lifetime of it.

Preparing is as important as delivering

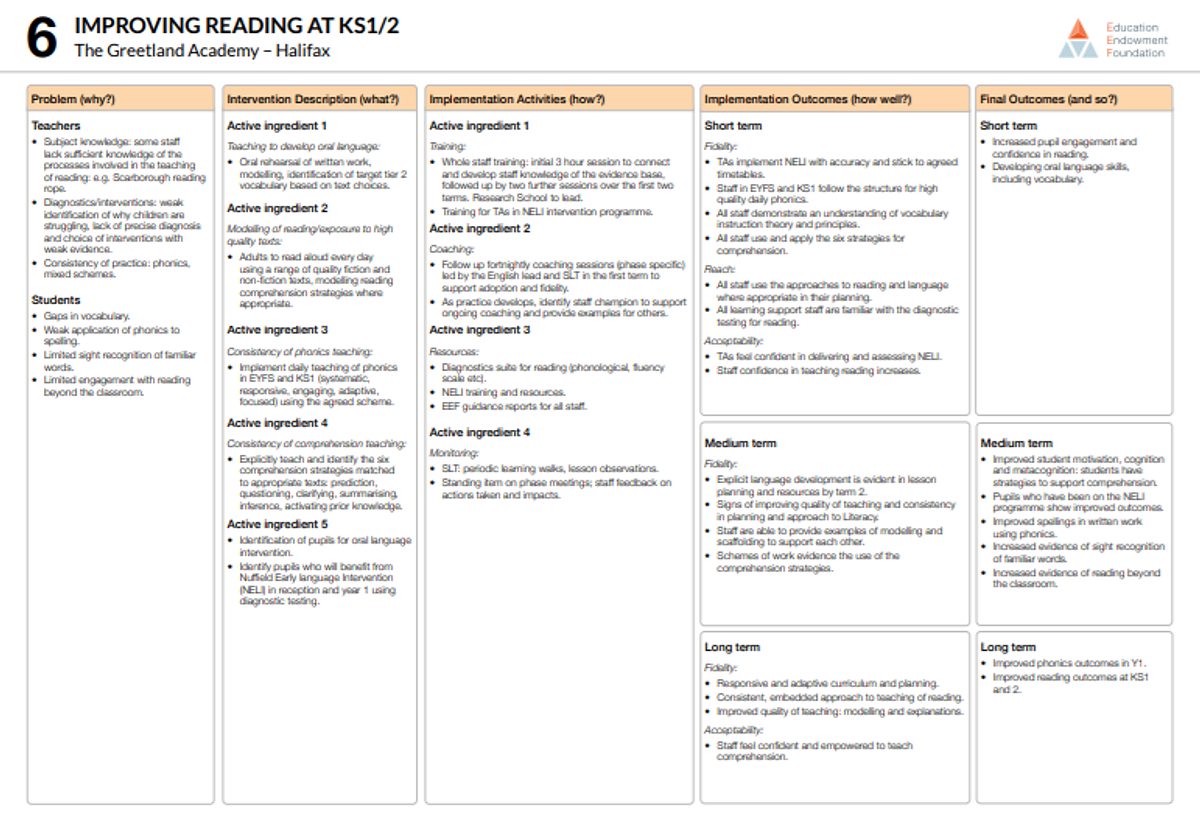

Seeing implementation as a process that can take a long time helps us to avoid the only emphasis being delivery. The ‘explore’ and ‘prepare’ phases of implementation are crucial and should be treated as such. Implementation plans can and should take time to write. They can take multiple iterations, highlighting challenges and prompting changes in thinking. You can find an bank of example implementation plans here.

By doing this thinking properly, and giving it the time it deserves, you will identify aspects of the implementation structure that can help you. Examples are given in the guidance report as to the kind of things this will involve:

And you don’t want to discover the need for these as you go along.

The right school climate

Recommendation 2 of the guidance is to ‘Create a leadership environment and school climate that is conducive to good implementation.’ But much of the time we create the right climate through good implementation.

And if teachers are being expected to enact multiple new programmes or policies at pace, with no lead-in time, along with their own priorities, then the culture we promote is not one that will give things the best chance to succeed.

Sign up for our newsletter here.

Blog -

We share questions and resources to unpick the EEF’s Voices from the Classroom

Blog -

Investing in Subject Knowledge has Multiple Benefits

Blog -

Success is an important factor in motivation – how do we reconcile that with desirable difficulty?

This website collects a number of cookies from its users for improving your overall experience of the site.Read more