Blog -

Teetering Off Balance: Avoiding Wobbly PD

Just because your PD has a balanced design, doesn’t mean it is stable

Share on:

by Bradford Research School

on the

Mark Miller is Director of Bradford Research School

There are no easy solutions to the challenges around pupil attendance. In previous blogs, we have suggested some approaches that might be beneficial:

Look beyond the headlines and identify specific challenges

Refine how you communicate with parents

In this blog, we consider three relationships that can be impacted by poor pupil attendance, and how we can restore them: self, others and curriculum.

Three relationships

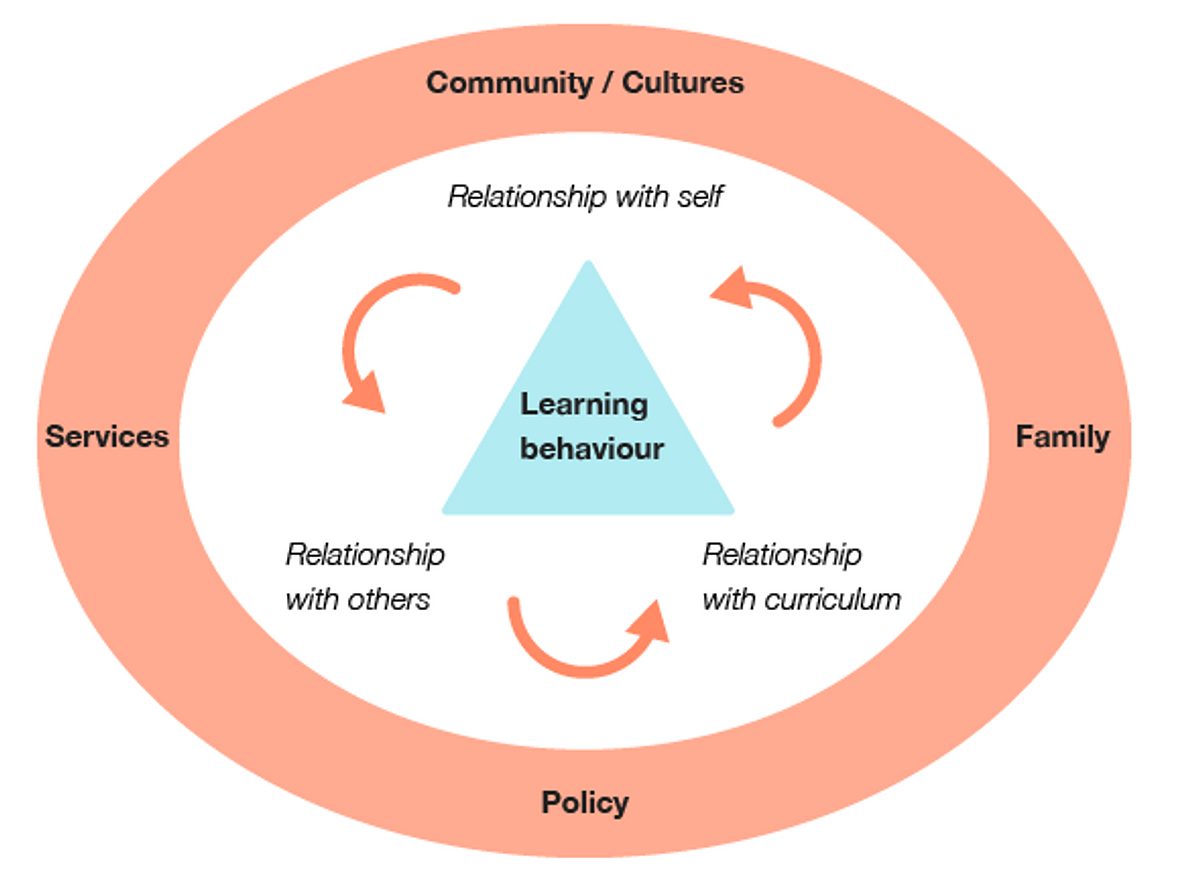

The behaviour for learning conceptual framework, adapted from Powell and Tod (2004), appears in the EEF’s Improving Behaviour in Schools guidance report. Central to any ‘learning behaviour’ lies three relationships:

Relationship with self, which could include elements like self-efficacy, confidence and resilience.

Relationships with others, which is the willingness and ability to form and maintain meaningful relationships with peers and adults.

Relationship with the curriculum, which means being able and willing to access, process and respond to the curriculum.

Relationship with others

Lots of interpersonal relationships can be affected by attendance. Friendship groups shift, class dynamics evolve and pupil-teacher relationships change. Our goal is to help pupils back in to these relationships.

In Motivated Teaching, Peps Mccrea writes about how we can ‘signal status’ to build belonging in a group. We do this by recognising contributions, particularly those that may be on the periphery, including everyone in all aspects and framing language in terms of we and us.

For pupils whose attendance is a concern, it may be helpful to prioritise adult-pupil relationships. One strategy is used by St Mary’s Catholic School in Blackpool: ‘The 2×10 model focuses on spending 2 minutes of non-school-related conversation with target pupils for 10 days to try and form a relationship, establishing a human connection beyond the usual learning focus of the school.’

School structures which promote group togetherness can help to make it easier to socialise. For example, a number of schools have ‘family dining’ where pupils and teachers eat together at lunchtime. Here’s an example from Dixons Trinity Academy:

Relationship with the curriculum

For pupils who are persistently absent, it is likely that they will have missed much of the curriculum. Not only will this mean that they have missed out on what has been taught, but they are at a disadvantage when it comes to acquiring new knowledge, as it is often a prerequisite. And teachers may have less knowledge about pupils’ areas of strength and gaps in knowledge.

We might not be able to easily cover everything that pupils have missed, but we should keep in mind ‘threshold concepts’, the key ideas that act as gateways for conceptual understanding in subjects. Instead of reteaching everything, start with these.

We may need to think more carefully about how we scaffold learning e.g. provide a knowledge organiser with some of the details that others in the class have learnt.

We can engineer moments of success, which remind pupils that they can engage well with the curriculum. These could come from simple moments like calling on the pupil for a question which you know they can answer e.g. following a mini whiteboard activity.

Relationship with self

How pupils perceive themselves can be affected when they miss school.

The other relationships can have an effect on this too. When a pupil begins to struggle more and more with the curriculum, their internal narrative can shift. It goes from ‘I am no good at fractions’ to ‘I am no good at Maths’ to ‘I am no good at school.’

Attribution is important. If pupils attribute something to factors outside of their control, they may lose motivation. Instead of ‘blaming’ poor attendance, which is in the past and cannot be changed, we should help pupils to focus on what can be done now. We should help pupils to focus on things that can be controlled, such as current effort, rather than things that they cannot.

This often comes down to specific pupils, but we should reflect on cases where pupils may feel less control. What if a pupil’s attendance is already below a threshold and they will never get it above it? What if poor attendance was due to factors beyond their control e.g. a family holiday? How do you support pupils with chronic illness?

We cannot go to the evidence for ‘off the shelf’ attendance solutions, but these three relationships give us some approaches which may be valuable.

Blog -

Just because your PD has a balanced design, doesn’t mean it is stable

Blog -

The EEF’s new implementation guidance report places a focus on engaging people

Blog -

We share questions and resources to unpick the EEF’s Voices from the Classroom

This website collects a number of cookies from its users for improving your overall experience of the site.Read more