Blog -

Learning Behaviours: Equipping Pupils And Staff With The Necessary Tools

Teacher at Billesley Primary School, Zainab Altaf, draws on personal experience & EEF guidance to explore SEL fundamentals

Share on:

by Billesley Research School

on the

Rob Laight, Evidence Lead in Education at Billesley Research School and Assistant Headteacher at The Coppice Primary School, Worcestershire, dissects evidence-based literacy strategies in this blog.

For the accomplished reader, Key Stage 2 is rich with opportunity: the opportunity to develop their knowledge to the full scope of the school’s curriculum; the opportunity to grow in confidence and motivation to read; and the opportunity to be moved by stories and to experience all of the wonderful things that great books can teach us. For the struggling reader, these benefits are, if not completely out of reach, significantly harder to gain.

A quick look at statutory assessment data between 2016 and 2019 tells us that there is a significant proportion of children who have not been able to reap the benefits of reading competency and who have been greatly hampered in their ability to access the next stage of their education. While there haven’t been statutory assessments for the last two years, all signs point to the issue being exacerbated further by disruptions to schooling in 2020 and 2021, particularly for disadvantaged children who are far more likely to have struggled to access books.

Of course, none of this is news. The literacy gap has been high on the agenda of schools for a long time — even more so now with the dominant narrative being one of ‘catching up’. If we are to ‘fill the gaps’ and ensure children do ‘catch up’ when we only have a finite amount of time to work with, it’s crucial that we identify the most effective and efficient use of this time, which should be informed by the existing evidence into what has — and hasn’t — worked in similar settings. In terms of improving the standards of primary reading, one way to use our time that holds a great deal of promise is reading fluency practice.

I must confess that I made it through three years of training and around eight years as a primary teacher without ever really thinking about reading fluency in great detail. It wasn’t a feature of the professional development I received and any writing about the subject didn’t cross my path. Fortunately, reading fluency has undergone something of a renaissance in the last five years. Thanks in no small part to sources like the excellent Herts for Learning KS2 Reading Fluency Project, the wider sharing of the work of people like Professor Tim Rasinski, and the EEF’s Improving Literacy in Key Stage 2 Guidance Report, reading fluency has gone from a ‘poor relation’ to something of a ‘secret weapon’, to a more prevalent part of the discourse around improving standards in reading.

As explained in depth in the updated Key Stage 2 Literacy Guidance, reading fluency is defined as reading with accuracy (reading words correctly), automaticity (reading words at an appropriate speed without great effort), and prosody (appropriate expression, stress and intonation). As the report states, reading fluency is often described as a bridge between word recognition and comprehension: accuracy and automaticity ensure that a child’s valuable working memory is not tied up with decoding individual words; prosodic elements of fluency are a useful way for children to demonstrate their comprehension. For developing readers, the importance of prosodic reading goes beyond impressing their teacher, as Schwanenflugel and Flanagan-Knapp describe in their 2017article:

We don’t just read expressively for an audience; we also read expressively for our own comprehension. Indeed, when you are having a hard time understanding something you are reading to yourself, reading the text aloud with good prosody can help.

If we extend the metaphor that reading fluency is a bridge between recognising the words and comprehending the text, it’s important to consider that some children might cross this bridge fairly independently if they read often from varied and appropriately challenging sources. However, for many children — particularly those who don’t have the privilege of a literacy-rich background — this bridge is a difficult one to traverse. That’s where guided oral reading practice comes in.

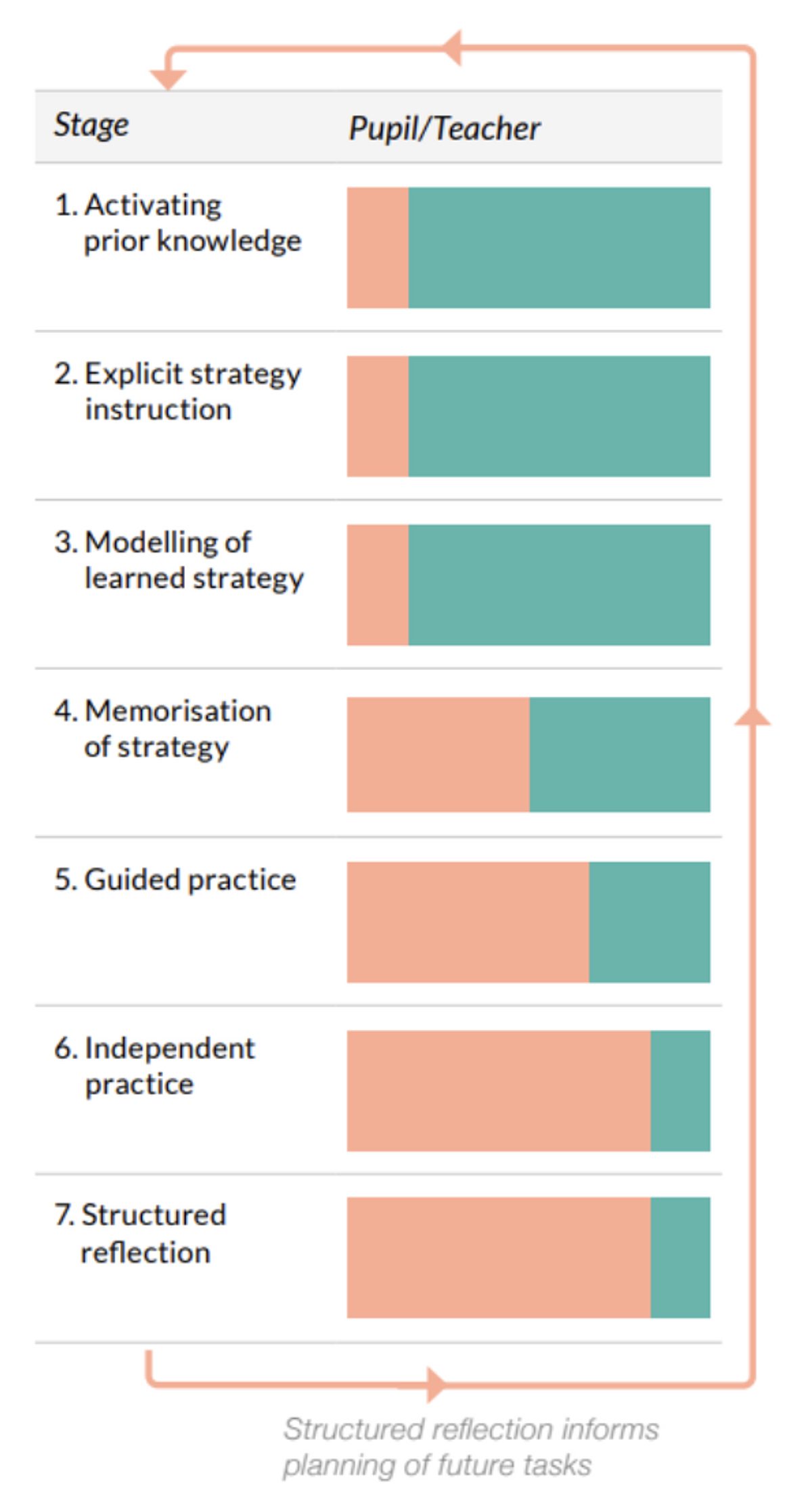

One of the reasons why I am convinced of the potential of guided oral reading practice — using strategies such as Reader’s Theatre, a new addition to the second edition of the KS2 literacy guidance — is because it mirrors what we know works in terms of the ‘gradual release of responsibility’ model that is exemplified in detail in the guidance report for ‘Metacognition and Self-regulated Learning’. In the remainder of this blog, I’d like to talk through how fluency practice is taught in my school using the gradual release of responsibility, while sharing some of the lessons I’ve learned about the details that have been key to making fluency practice work in my setting. While fluency practice can — and in my opinion should — be facilitated with a balanced diet of text types, the example below is based upon using the class novel for practice for the sake of brevity and accessibility:

1. Activating prior knowledge

This is a short and sharp part of the lesson which is designed to ‘set the scene’ for the fluency practice we’ll be undertaking in the lesson. It might involve asking quick ‘show me’ questions using mini-whiteboards that are designed to recap the most important information from the previous chapter. Another of my favourite strategies is to write a post-it note summary of each chapter of our class novel to keep on a cumulative summary display; this way, lessons can begin with a rapid recap of ‘the story so far’ (a bit like a previously on… introduction to a serialised TV show). In my experience, a little and often approach to teaching the strategy of summarising does far better than attempting to teach it as a discrete skill. This strategy also follows the gradual release of responsibility, with the teacher modelling how to summarise an extract in the early stages of a novel, composing with class contributions as they develop their understanding, and finally turning responsibility for summarising over to the children through partnered talk and questioning once they’ve shown good understanding of how to summarise. This part of the lesson may also include the teaching or revisiting of tier 2& 3 vocabulary that appears in the day’s extract.

2& 3. Explicit strategy instruction and modelling of learned strategy

Following the activation of prior knowledge, the teacher will then read aloud from the text, modelling expert prosody. A passage (not necessarily at the start of the day’s reading) will have been chosen for children to practise their own fluent reading. Choosing the right text or extract here is key — it should be challenging enough that the children wouldn’t decode it comfortably in an independent manner, but at a level of challenge that’s attainable with teacher modelling and scaffolding.

In my school, we use the term ‘performance reading’ to refer to a prosodic, meaning-laden style of reading and regularly share the importance of practising performance reading aloud to train the ‘performance reading voice in your head’. Performance reading in my school is comprised of 6 Ps:

- pace

- pitch

- pauses

- punctuation

- personality

- power (I know this last P is a bit contrived — we use it to refer to whether something should be read loudly or quietly, as well as whether any words are emphasised and given more power than others).

Whatever framework you choose to use, there is plenty of value in having a common language to talk about reading prosody. At this stage of the lesson, the teacher might ‘cue the children in’ to what they should listen for (I’m going to read a part of the story now where the characters are going into a scary new setting — pay special attention to the way I use pace and pauses to create tension). In the early stages, it will pay to focus on one or two aspects of performance reading, scaling up as the children become au fait with the different terms.

The teacher will then model reading the passage aloud in a way that best illuminates the meaning of the text. Depending on the teacher’s assessment of the class, this might involve a slightly slower than natural prosody or giving extra emphasis to certain words or phrases, so that the children’s attention is drawn to salient parts of the text. The extract should be between a minute to two minutes long so that the children do have to use their decoding skills when they practise, and this modelled read is usually timed — the message being that you’ve done a good job if you’ve taken roughly the same amount of time as your teacher, not if you’ve read the fastest.

4& 5. Memorisation of strategy and guided practice

What happens at this phase will vary depending on the age and experience of the children. At the simplest level, it might involve asking children ‘what did you notice?’ or ‘what happened to my reading when…?’ and using echo reading to practise certain sentences or paragraphs. With children who have had plenty of practice of performance reading, we might complete some text marking, annotating the text using an agreed code to show where extra emphasis is placed, to show rising or falling pitch, or to ‘scoop’ words and phrases into clause or sentence units. This marked-up version of the text then acts as a guide for their own practice. Much like cumulative summary, the process of text marking undergoes its own gradual release of responsibility over a series of lessons.

6& 7. Independent practice and structured reflection

The children should now be ready to attempt the challenge of decoding the text independently and with increasing fluency. They do this with a response partner — one pupil will read the text while the other follows the text with a ruler. At the end of the extract, the listener should offer feedback about what went well and what might be improved in the next practice before the children swap roles. The teacher’s role at this stage will vary — in the early stages of implementing fluency practice, they will need to ‘be seen listening’, walking the room to listen to as many groups as possible and ensure that agreed routines are being stuck to; as the children become more familiar with routines, the teacher’s role can transition more to guiding practice and supporting children who might find reading difficult. There is a solid evidence base for repeated oral reading, so children should be given time to practise their extract multiple times, aiming to achieve greater fluency each time with the support of their partner. After each child has been able to have a number of attempts at the text, partners should offer feedback on words/phrases that were challenging and reflect on their reading using the language of the 6 Ps. At the end of the session, which will ordinarily follow further modelled reading by the teacher, we would complete a summary for our cumulative summary wall (with the teacher exercising their judgement about which stage of the seven-point model this should feature).

Even more so than usual, embedding guided oral reading practice effectively is reliant on teachers ‘sweating the small stuff’. To use the time well, teachers need to establish clear routines and make those routines ‘routine’ by sticking to the details until they are automatic. For this reason, guided oral reading practice can be made more powerful if used in small-group interventions rather than whole-class settings, where a teacher more easily monitors and directs children’s practice. Additionally, the partnerships in the class need thorough consideration as they can make or break the lesson. I advocate mixed-ability pairs (with ability here referring to the pupils’ performance on oral reading fluency assessments) with the stronger reader going first, thus providing an extra model or support to a less fluent reader. Teachers need to think through the pairings in their class so that the relationships between peers are trusting and supportive, and so that any gap in performance doesn’t cause embarrassment to one of the children. There needs to be sensitivity, too, about the children with specific barriers to oral reading fluency such as speech impediments.

Although there are many things that a teacher needs to consider when planning for reading fluency practice, the time that it takes in lessons is pretty small. I’d argue that it’s a good use of a little time. Moreover, the process to plan and prepare for a reading session like this is actually fairly short and simple:

- find a challenging text with high ‘potential’ for modelling an aspect (or aspects) of reading fluency

- identify vocabulary and phrases (e.g. idioms) that will present a particular challenge in terms of decoding or understanding

- possibly rehearse a ‘performance read’ of the text to the point of confidence in modelling

- invest lesson time in the teaching and maintenance of routines so that they become the norm

I’ve only really discussed ‘the tip of the iceberg’ here — there’s plenty more to consider when it comes to embedding good practice for reading fluency in school. Similarly, it’s important to stress that fluency practice alone won’t be sufficient to transform struggling readers into accomplished readers. For example, it will need to be taught within a reading offer across the curriculum that builds children’s background knowledge and vocabulary, alongside the effective teaching of comprehension strategies (which I’ve written about here), and with effective diagnosis and extra phonics support for children who struggle to decode. That said, engaging in fluency practice in the classroom is a good use of a little time. While it may not be a panacea, fluency practice should form a significant part of the evidence-informed teacher’s repertoire when it comes to improving standards for children’s reading in Key Stage 2. If we can make it a regular habit in the Key Stage 2 classrooms, giving thorough thought to the details that make it work, it should go a long way towards helping a greater number of children to ‘cross the bridge’ to become accomplished readers, with the myriad benefits that brings.

Further Reading

EEF (2021) Improving Literacy in Key Stage Two Guidance ReportEEF (2018) Metacognition and Self-regulated Learning Guidance Report

Galway, M, Herts for Learning (2021) A Field Guide to Reading Fluency: a Reader’s Digest of our Work to Date

Schwanenflugel, P.J. & Flanagan Knapp, N. (2017) The Music of Reading Aloud, Psychology Today

Rasinski (2012) Why Reading Fluency Should be Hot!, The Reading Teacher Vol 65 Issue 8

Such, C (2021) The Art & Science of Teaching Primary Reading

Blog -

Teacher at Billesley Primary School, Zainab Altaf, draws on personal experience & EEF guidance to explore SEL fundamentals

Blog -

Our Evidence Lead in Education, Martin Hill, uses his own experiences & EEF guidance to give an honest, accessible guide to SEL

Blog -

Claire Bennett, Teacher at Billesley Primary School, draws on her experiences as a practitioner to help expound EEF guidance

This website collects a number of cookies from its users for improving your overall experience of the site.Read more